Idon’t remember the first day I hated my body, but I know I was around the age of 12. Almost overnight, the purely functional form that I existed within became a new social problem. Enrolled in an all-girls school, crushes and boys hadn’t yet entered the mix, but somehow, we all just knew which bodies were right and which were not. Mine was wrong; a round face still cloaked in baby-fat and thick thighs suddenly delivered by puberty were not a ticket to the top of the social heap.

From the very first day I thought something hateful about my body (likely something about my thighs—the first and perpetual bane of my existence), I can say with confidence that a day hasn’t passed since those thoughts were not a part of my inner monologue. If asked to list the body parts I like enough not to change, it would take moments (ankles and wrists—very shapely), while listing the opposite, i.e. parts of myself I would adjust, could occupy hours. Not that I’d actually tell anyone… I try not to talk about it.

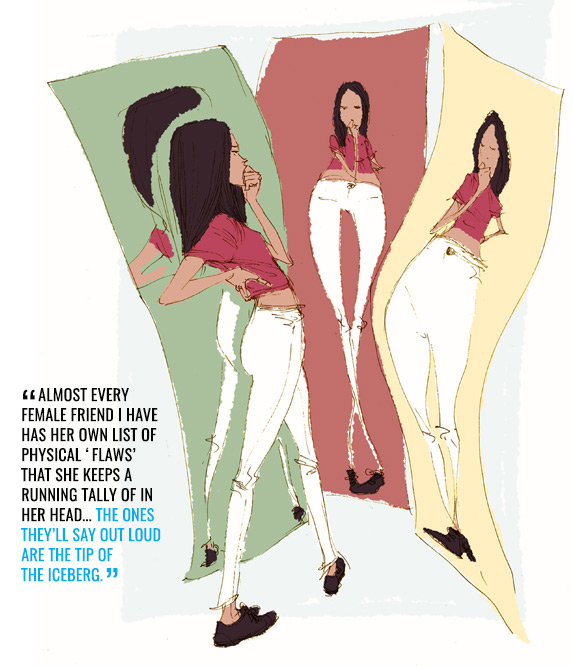

And I’m certainly not the only one. Almost every female friend I have has her own list of physical “flaws” that she keeps a running tally of in her head. The ones they’ll say out loud are the tip of the iceberg. I am not in their heads to hear the mean little comments their own inner voices throw at them in the mirror.

My own mental narrator runs a constant commentary about my body. She scouts each room to compare me to the other women in it, pointing to each that has thinner arms, better legs, a flatter stomach and/or a perfect ass. She reminds me when I’m the biggest person at the dinner table, or that the girl across from me would look so much better in my outfit. FYI: She’s often lying.

When I recently let her words slip out of my mouth to a friend, comparing myself to another woman at a party, she looked at me with a mix of shock and confusion. “Do you really think you’re bigger than her? You have body dysmorphia” she said, flatly stating what I already knew. It’s not that I always think I’m bigger than I am. The complicated trickery of this inner voice causes me to mostly see myself as bigger, but sometimes smaller and, occasionally, accurately. There’s no way to tell which is which.

It’s confusing and painful to always see something different when I look at myself. At times it’s led me to lose weight, follow strict meal plans and dive into rigorous exercise regimes, while at others the exhaustion of listening to the voice has led me to just accept it as part of the wallpaper and begin not taking care of myself at all, gaining weight and adding more items on the tally that my inner voice can list as a flaw. Even when I feel that I’m at my optimum weight, the voice is there with a list.

Stating the obvious, this type of issue has far-reaching effects in a person’s life. Self-consciousness makes me sometimes withdraw in social settings. Every romantic partner has to deal with the insecurity I only show when my guard is down, the secret worries that my body isn’t attractive, no matter what size I am. It has jeopardized my health, both mentally and physically. Women who live with these self-critical “mean girls” in their minds often suffer from anxiety, depression and low self worth. And, because of this, they also often allow themselves to be treated poorly, mistakenly believing that they don’t deserve better.

I’m not cured of this issue, but as I get a little older, I’ve grown aware of this cycle of self-abuse, rather than just blindly repeating it. The answer on how to break out is unique for every woman (or man) who feels trapped in the cycle, but there are a few steps that seem to universally help.

First, face that there is a problem and decide to address it. While it’s easy to just throw your hands up, say “well… this is who I am” and live in the spin cycle indefinitely, this option is the opposite of helpful. Think of it this way, if there were an actual person in your life that was saying mean things to you on a daily basis, you would know something must be done about this behavior, but because the voice is yours, it can feel like you just have to live with it. Only by admitting to yourself that something is wrong, will you be able to do anything about it.

Second, find help. The key here is to choose resources that are equipped to really help you, based on what works best for your particular needs. There are counselors who specialize in body issues and eating disorders, as well as group meetings that can form a community of support. You may find that writing about it on your own will be a good way to start (hence, this column for me). Maybe you need to take long walks to let your mind process all of your negative thoughts, or find a yoga or meditation practice that helps you centre yourself. What’s most important is that you look for outlets outside of your own normal support system. These issues should not be the exclusive burden of your family, friends or romantic partner. They are too close to the issue; their feelings are too clouded by love or worry or exasperation, to really be able to advise you. Still, you will want to acknowledge to your loved ones that this is a problem for you, one that you are working on it. You’ll also want to advise them of things they do or say that may trigger your self-critical voice. That said, do not hold others responsible for “fixing” you; at the end of the day, we all have to do that heavy lifting ourselves and face the voice in our head.

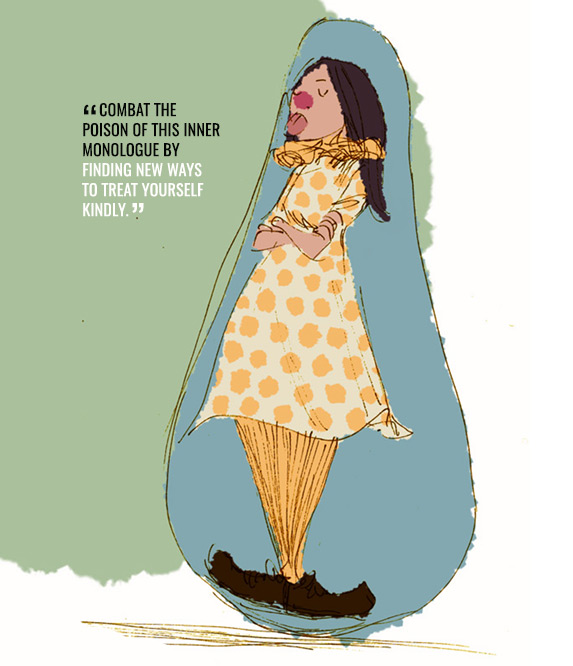

Third, combat the poison of this inner monologue by finding new ways to treat yourself kindly. Take time to do the things you enjoy, even if it means doing them by yourself. If you are busy thinking about the amazing book you just read, or the band you saw, there’s less space in your brain for the mean girl residing in it to weasel in with her barbs. Exercise regularly—completely separate from weight-related goals—to remind yourself that your body is useful beyond just as a visual object to be critiqued. Feel your body get stronger as you challenge yourself to do more with it, and you’ll find that it will be that much harder to think of your body as “gross,” “undesirable” and “useless.”

Finally, remind yourself that you are not alone. Everyone is damaged and broken in their own way. People who you think look perfect—whose bodies you’d do anything to look like—they may hate themselves too. Maybe not the exact way that you do, but they have their own deep wells of insecurity and panic—everyone does. Being anxious and hard on yourself is part of the human condition. Cut yourself a little slack. Most of all, try and create a friendly inner voice to stand up to your bully. Defend yourself the way you’d defend your best friend if someone were saying mean things about her. See if you can balance mean thoughts about yourself with kind ones.

There are no simple answers, and I admit that my “tips” here cover just the beginning of the struggle. It might seem like we need to learn to be kinder to ourselves as we get older, but I think it might be the opposite. We need to relearn the simple affection we had for our own bodies as children. I’d love to wake up and feel the way my childhood self did about my own form, with a happy indifference that allowed me to focus my attention on the rest of the world around me. These problems may seem as navel-gazing as they come, but they have to do with more than just our ego and vanity. They are born out of the way our bodies are treated by the rest of the world. Reclaim the gaze and re-establish kindness to your own most important property: yourself; this is one of the keys to a happy, fulfilling life. All any of us can do is try… and try again.

In short, treat yourself the way you’d like to be treated. The golden rule never did hurt anyone.