I have always loved Jane Austen’s novels. Love overcoming obstacles, and the smart girl winning out in the end, regardless of dim-witted relatives and/or social obstacles thrown in her path. It all appealed to me, but no character rang more true than Emma.

Slightly (or more than slightly) spoiled? Definitely. But Emma was wise beyond her years, and always wanted to take care of those she held dear. And what better way to take care of them, than to find them love? While she may have been proven wrong again and again, when it came to her match-making impulses (Mr. Elton and Harriet Smith, or in more modern Clueless parlance, Elton and Tai? Terrible match!), her good intentions made up for her hubris in my eyes. That said, if there’s anything I learned from that classic tale, it is that meddling in the love lives of others is likely to bring stress—even pain—onto oneself.

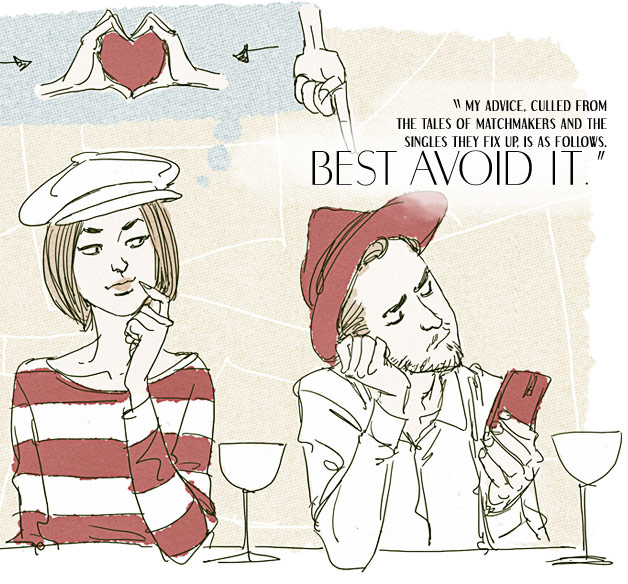

I have heeded Emma’s lesson in my own life as much as possible. While I love dreaming up combinations of single friends that might hit it off, and have gone so far as to engineer a run in or casual, circumstantial hang out, my hope has always been that said friends will take it and run with it from there. Many people I know haven’t been so lucky (maybe they should have spent more time nerding out over Ms. Austen like I did), and the results have been rarely pleasurable for any of the parties involved.

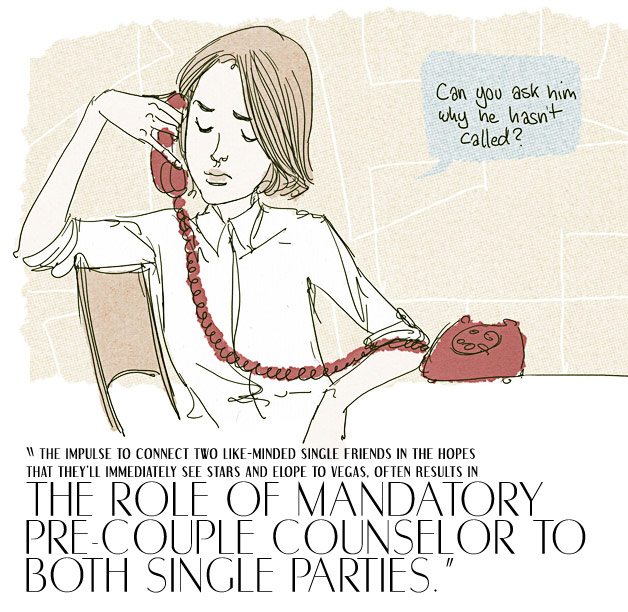

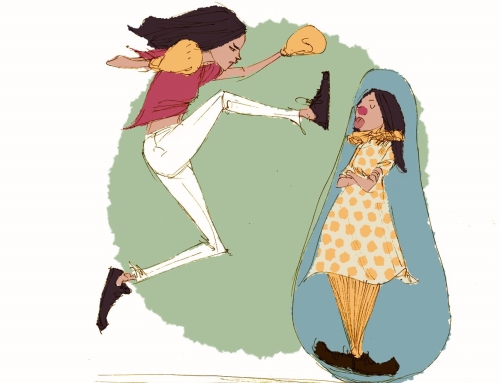

Matchmaking, it turns out, is a fraught business. What appears innocent enough—the impulse to connect two like-minded single friends in the hopes that they’ll immediately see stars and elope to Vegas—often results in the role of mandatory pre-couple counselor to both single parties.

One friend, let’s call her Jemma, has recently sworn off matchmaking after many years of enthusiastic attempts. Amongst her landscape of friends, she always seemed able to find two individuals with enough in common to make a good match on paper, but unlikely to happen upon each other unless a mutual friend decided to manufacture the link and introduce them. The problem for Jemma, it turned out, was that these matches would immediately become her personal responsibility.

“If the first date went well, I would hear from both of them,” Jemma recalls. “But if it didn’t, I would just hear from the one who was more into it, hoping that I had heard from the other and could pass along intel.”

And so it went; when someone didn’t get a follow up text for a second date, or even if their own texts weren’t returned fast enough, Jemma would hear about it. And, if after a few dates the more interested party received a gentle, friend-zone style brush off, she was definitely going to have to hear about it. As for the brusher-offer, the one who hadn’t been into it, well they were apologetic at best and awkward or even offended by the “dud” set up at worst.

The flipside of this was no better. When one of her matches went the distance, her role as go-to counselor and advisor was extended, drawing her into the kind of “what is he/she thinking??” conversations that are mind-numbingly terrible when you have no involvement, and perceptively worse when you can technically be held responsible for the emotional pretzel your friend has worked themselves into.

For good reason, Jemma has recently decided to hang up her quiver and arrows, and call playing cupid quits. The return on investment in terms of her time and brain cells was just too low to keep going.

In my research in this topic, my female friends were generally wary of fixing up friends. My male friends were more open to the subject, although less likely to experience the after-effects that Jemma described, as they were clear about having no interest in helping or fostering the relationship after making the initial introduction. One interesting phenomenon that both male and female single friends have described is that of fix ups that were clearly wish fulfillment on the part of the fixer-upper.

Multiple people described having been pushed into a date or conversation with a person just because they happened to be single and the friend doing the pushing was not. Basically, they would be set up with people that their friends wouldn’t necessarily think they’d they would like, as much as people their friends themselves would date if they were single. The priority in these cases wasn’t making a match, as much as living vicariously through a single friend, while still staying in the bounds of their relationship.

All things considered—Ms. Austen, Jemma the ex-matchmaker and gloomy research results—basically, my advice is as follows: best avoid it. If you truly believe you have two single friends that are bound to fall in love if they meet, it’s simple enough to invite them both to the same get together and let nature take its course. Anything further, and you’re wading into waters that are more likely to cause headaches for yourself, or side eye from friends assuming that the person you’re foisting on them is someone you yourself would like to take home, than any kind of happily ever after. In fact, technology is with me on this. It has kindly taken such matchmaking duties over for us now; Tinder tells people who they and their matches have in common on Facebook. If you get a text from a friend asking for your thoughts on a potential suitor they’ve swiped right to, by all means weigh in. Just consider adding a caveat that you aren’t in fact a reference in this person’s dating resume. If we can learn anything from Jane Austen—especially my personal heroine Emma—it is that true love laughs at our plans to steer its course.