There’s something in the raspy wash of Ben Knox Miller’s voice that transports you to a woodchip floor bar in some mining town just off Route 66. The front man and lyrical grace behind The Low Anthem, Miller, together with band mates Jeff Prystowsky, Jocie Adams, and newest member, Mat Davidson, delved deep into the American psyche with Smart Flesh, the follow up to their second record, the critically-acclaimed Oh My God, Charlie Darwin.

Composed and recorded in a 40,000 square feet defunct pasta sauce factory — where band and guest artists lived for the duration of the creative process — the album, with its mix of banjo, pump organ, and transistor radio, amongst a dozen other instruments (of which the members frenetically switched between), almost demands being played on a phonograph to a whiskey accompaniment.

Mood ranges from the proclamatory howl of “Boeing 737” — the imaginary monologue of a man who shared a drink with French high wire artist Philippe Petit the day the Twin Towers fell — sung over top the fierce clamour of percussions, to the quiet redemptive hymn of the album’s title track, “Smart Flesh.” Touching the poetic grit and sensitivity of Dylan Thomas, Miller exposes the souls of the lost and unfound with this and tracks such as “Apothecary of Love,” while angling the mirror before the modern American dream in “Golden Cattle” and “Hey, All You Hippies.”

Currently on tour, FILLER caught up with Miller, before he boarded a trans-Atlantic fight to Europe, to talk about The Low Anthem’s recent release, and writing the genuine back into songwriting.

So first off, the pasta sauce factory. I imagine living composing and recording an entire album there must have had quite the influence on the end sound of Smart Flesh?

Yeah, see that’s the idea. The sound happened in that space. Those were the walls that resonated, sculpted the frequency. That’s what the mics captured. It’s not a close-mic-and-process record. Nothing like that.

Were you in a different headspace while living in that space?

Yeah, lots of space for our heads, but look out! A swooping bat. Also, make sure to wear a warm hat. Headphones are kind of like earmuffs, so that was helpful. They let us out sometimes to go to Dunkin’ Donuts. It wasn’t long before our cycles began to align and things took their natural pace.

Guessing that the unexploited charm of the factory might have something to do with the death waivers that the landlord had you and all the others sign?

He was just covering his ass, which is understandable. I signed quickly suspecting that if I died, I would be unconcerned with liability.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=7D3v9VkCdjQ

Must be strange going from such a reclusive living situation to touring?

Yes! And people wonder why we are so awkward in person! We’ve been living in a caves eating lichen and ladybugs. We’ve developed our own dialect. It’s not easy.

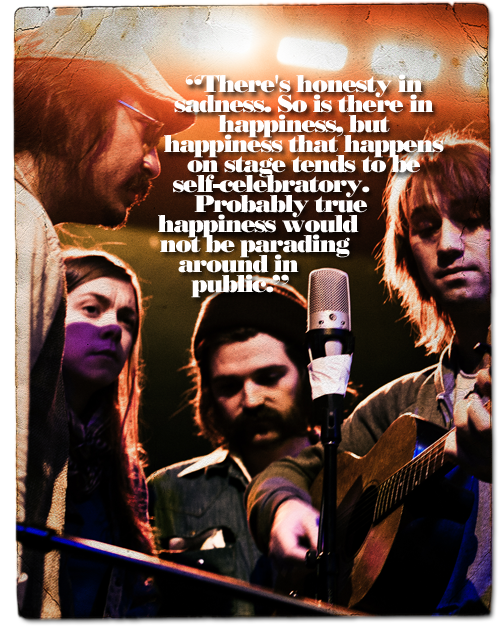

Reclusive living has its benefits though, lots of time for reflection useful for songwriting. When it comes to this, your thoughts seem to tend towards the sadder things in life. What do you think it is about sad songs that speak to people?

People are sad. There’s honesty in sadness. So is there in happiness, but happiness that happens on stage tends to be self-celebratory. Probably true happiness would not be parading around in public. It would be in repose on some remote cliff shelf or free-diving with whales.

When you’re writing, do you use much of your own experiences as inspiration for the lyrics?

I don’t much believe in inspiration. Writing is craft to me. I try not [to] flee my own songs when I find myself iced inside of them, but I have no intention to be or not to be there.

You’re obviously doing something right with the amount of critical praise you and the band have received, including being called the most important American band playing today by one music critic. What do you make of the reviews?

Heavens, has my mother been blogging again?