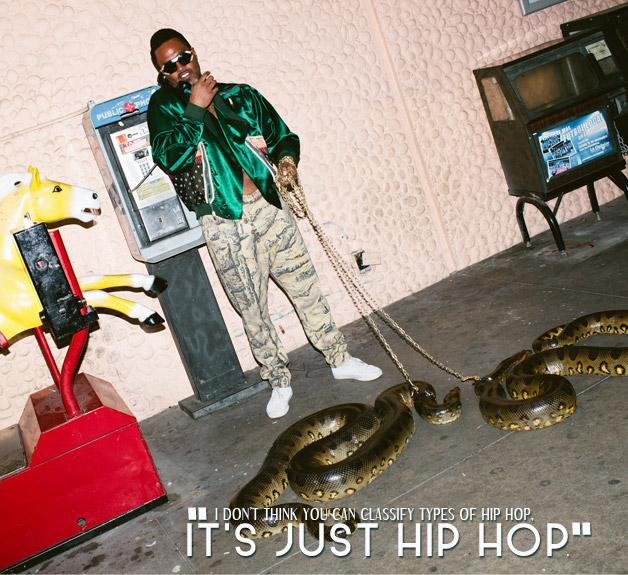

Interviewing Shabazz Palaces’s frontman Ishmael Butler is just as experimental as the Seattle hip-hop duo’s space age sound. It’s clear from the get go that Butler isn’t interested in defining where he and his musical partner, Tendai Maraire, stand on the grand spectrum of the genre, in fact, they aren’t too sure themselves, and they like it that way: left exploring in the haze.

It’s also apparent that any sort of standard question pontificating the deep inner mechanisms of music, particularly what has defined, or now is redefining, hip-hop, are off the table. Genres and categories are not something the musician endorses, making it senseless to talk about breaking free of their boundaries.

In other words, there’s a towering stonewall between my questions and Butler’s musical process. I’m left with only the music to decode, but as the artist reassures me, “It’s all good baby,” the answers are there in the music anyway.

And the music says volume. On their latest record, Lese Majesty (the duo’s second album), there’s everything from jazz harmonies to EDM beats, twisting through funk, R&B and rap rhythms. Quite possibly indefinable, the experimentalism that is Shabazz Palaces has critics praising the musicians as “the future of hip-hop.” But this doesn’t phase, Butler, again, to do so would be to acknowledge the existence of genre barriers in the first place. “I don’t think you can classify types of hip-hop, it’s just hip-hop,” declares the musician.

For us, Butler is still definable in some ways. He’s a music radical and a nonconformist. His artistic vision has evolved since his Digable Planets days during the early ‘90s, now leaning more towards the electronic stylings of Gary Numan than that of Thelonious Monk’s bebop sound. And, quite notably, he’s an artist committed to change and the alternative. Just take his name for instance, born Ishmael Butler, turned Butterfly for Digable Planets, he now prefers to go by Palaceer Lazaro. Hey, who ever said you had to stick to one pseudo name in a lifetime? That would sound suspiciously like a rule if it were stated, and Butler isn’t about rules.

For a hip-hop artist to create the most celebrated and exciting music of his career, over two decades after his musical debut, is more than an unlikely notion, it’s revolutionary in Butler’s and Maraire’s case. And while the hip-hop artist makes it clear during our interview that the label “experimental” is not something Shabazz Palaces lets define them, it’s hard not to use the descriptor when no one word but a wide-adjective like “experimental” could encapsulate the brain-bending, utterly entrancing opiate-like music the group is creating.

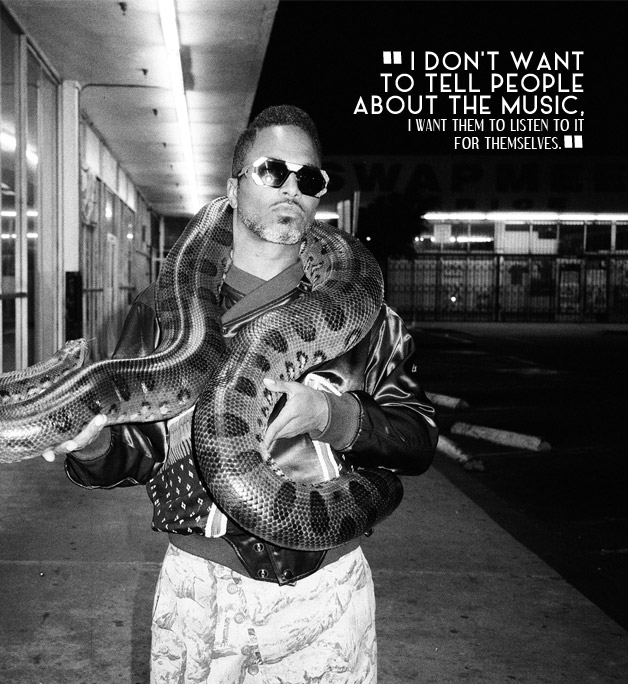

The duo’s latest album exemplifies Shabazz Palaces’s scope (and pop culture is demonstrably well within their reach) with a collection of 18 tracks called things like “#Cake” and “New Black Wave.” Even the album, wrapped in an embossed, faux-sharkskin sleeve, which boasts receiving its world premiere — complete with accompanying light show — at Seattle’s Pacific Science Centre Laser Dome, is something to marvel…and Instagram.

All things considered, the most pioneering aspect of Lese Majesty is though that it shies away from the egocentrism of modern hip-hop. Having described the album as a “sonic attack on the ‘me-mania’ that’s sweeping over our culture of late,” in a previous interview, Butler suggests that there’s intent behind his abolishment of genre definers. He deliberately makes his lyrics incoherent by use of heavy reverb and delay, while letting the occasional phrase slip through for the listener to interpret. No façade of models popping bottles here; reality is in the music, you just have to listen.

“I don’t want to tell people about the music, I want them to listen to it for themselves and decide what it’s about,” explains Butler more than once during our talk.

A master of deflection, the musician is notorious for avoiding direct answers during interviews; and so, whatever truly inspires Butler’s music remains a mystery for each listener to solve/interpret on their own. The only thing he’ll say about the origins of his sound is that he owes his parents thanks for supporting his decision to make music in the first place.

The rest of the conversation Butler is interested in having is one likely had on a barstool rather than a formal interview setting. The only point he keeps coming back to is that he’d rather people listen to the music than read an interview or review about it. Should I be offended? Why should I be, as he keeps reassuring me, “It’s all good baby.”