In the ever-expanding modern art forum, ironic commentary on mass cultural and generational angst has so littered the landscape that sincerity is now persona non grata. He’s the narc at a high school kegger, biding his time, chugging from the funnel till the moment he outs the coterie of “artists” that trusted his disguise to be like their own.

“I don’t fuck with irony so much, myself,” says Nate Lowman, the 32-year-old wunderkind of New York City’s young art scene. “It’s not my favourite tool for participating in culture.” The exception to the “If it looks like a duck…” rule, while paparazzi snaps of a dishevelled Lowman dressed in hipster uniform, hand-in-hand with one-time girlfriend and faux-poor tastemaker Mary-Kate Olsen, may clutter the blogsphere, Lowman is not an individual deducible according to appearances.

His mother was an English teacher and his father was the principal of a non-profit art school he founded in Lowman’s small hometown of Idyllwild, California (population roughly 2,200), situated in the mountains above Palm Springs. Despite his father’s involvement in the arts, Lowman insists dad was “a principal nonetheless. […] I grew up with rules to break.” Raised away from traffic lights and surrounded by desolate forests, Lowman receded into his “unrealistically beautiful” environment, and was something of a loner until his move to the big city. He says, “After living in New York for a short time, I became uncomfortable with the quiet, and not so good at being alone.”

An anointed member of this cultural hub’s elite inner art circle, Lowman — who counts iconic photographer/painter Richard Prince as a mentor and close friend — credits the city for his ongoing evolution as an artist. “I live in New York because there is a culture here for what I do,” he says. “People give a shit about the same things as I do here.”

While some art critics judge Lowman’s art to be derivative, self-conscious appropriations of cultural artefacts, wanting, as New York Magazine’s Jerry Saltz does, to box him in with what he labels the “new hip academy,” characterized by “bad-boy shtick and hammy caricature,” the artist — in his flannel shirt, skinny jeans and mop of bed head underneath a straw boater’s hat — remains one of the most talked about young artists working out of New York, showing at esteemed museums and galleries including The New Museum, the Guggenheim, and Maccarone gallery, where Lowman will premiere another exhibit come April 30th , scheduled to run till June 18th in conjunction with the neighbouring Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

Quietly intelligent and quick to correct any misgivings one may have about the sort of Bohemian upbringing that might have given him the one up on his current vocation (“I was lucky to have access to art and grow up around the arts. But growing up in the ‘90s, in Riverside County, becoming a crystal meth head would have been an equally natural outcome”), Lowman isn’t one of the laissez-faire bad kid art types that assumes the honour of acting voice of a generation whilst putting more thought into their arsenal of interview quips than their actual art work. Unlike these folk, whose work 9 times out of 10 hinge on a grasp at irony rather than anything resembling artistic talent, Lowman prefers a less heavy-handed approach. “Irony, like humour, is everywhere. I think that Generation X, the one before mine, really set some forest fires with irony,” replies Lowman when asked if genuine commentary in art has become a near impossible feat. “They were like bombs over Baghdad with the irony.” But, as the artist believes, and as his own body of work demonstrates, “irony can be genuine commentary the same way humour can be genuine commentary.”

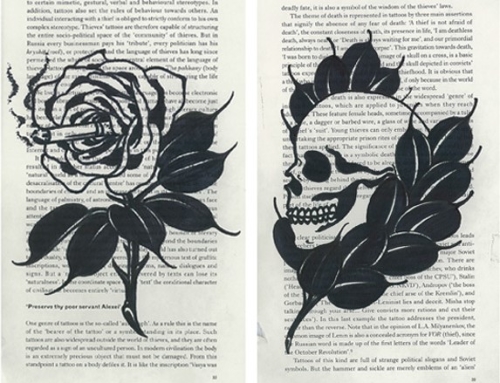

A multi-media artist, Lowman’s work spans from pop-infused portraitures of friends, including art dealer/curator Clarissa Dalrymple and fellow N.Y. artist Dan Colen, to the semiotic machinations of installations featuring found objects such as antique gas pump frames, to a culturally-loaded smiley face series inspired by the mad scribblings of O.J. Simpson to fans during the Nicole Brown Simpson murder case, in which he turned the “O” in O.J. into a smiley face. But, as Lowman asserts, though art critics know him for his framing of existing cultural artefacts and iconographics that weigh in heavy on the Zeitgeist, the business of recoding and deconstruction are not the single purpose of his art. “Making claims and reclaims is for Manifest Destiny and bureaucrats,” declares Lowman. “There is a vast amphitheatre of clichés that speak of the relationship between art and life, trash and treasure, love and hate. In some cases, to simply present an object is the best way to represent it in order to challenge these platitudes. Other times it’s necessary to alter the original material in some way. It’s the treatment of the object that re-imagines the subject.”

Take Lowman’s portraitures of the now infamous image of Miley Cyrus in the embrace of father Billy Ray Cyrus, taken from the controversial Vanity Fair editorial shot by Annie Leibovitz; despite speaking to the popular conscience, the artist consciously avoids talking at his audience here. “When I’m painting images from the newspaper I feel like I’m acknowledging ghosts,” shares Lowman. “Art comes after nature and makes life more complex.”

In preparation for his upcoming show at Maccarone gallery, including a series of 20 paintings inspired by Willem de Kooning’s canvases of Marilyn Monroe, Lowman takes a moment to talk art, curating, and critical success.