A truly great classic never seems to fade from print, its story timeless. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, better known as Alice in Wonderland, published more than 150 years ago, influenced generations of artists with its marvel, absurdities, and universality. Lewis Carroll’s found the artwork in the timeless novel equally as important as the tale itself. Still preserved and on display at the Tate Liverpool are Carroll’s own drawings and photographs, alongside Victorian Alice memorabilia and John Tenniel’s preliminary drawings for the first edition of the novel. The exhibition simply takes the title of the classic work and displays generations of artistic interpretations of the story.

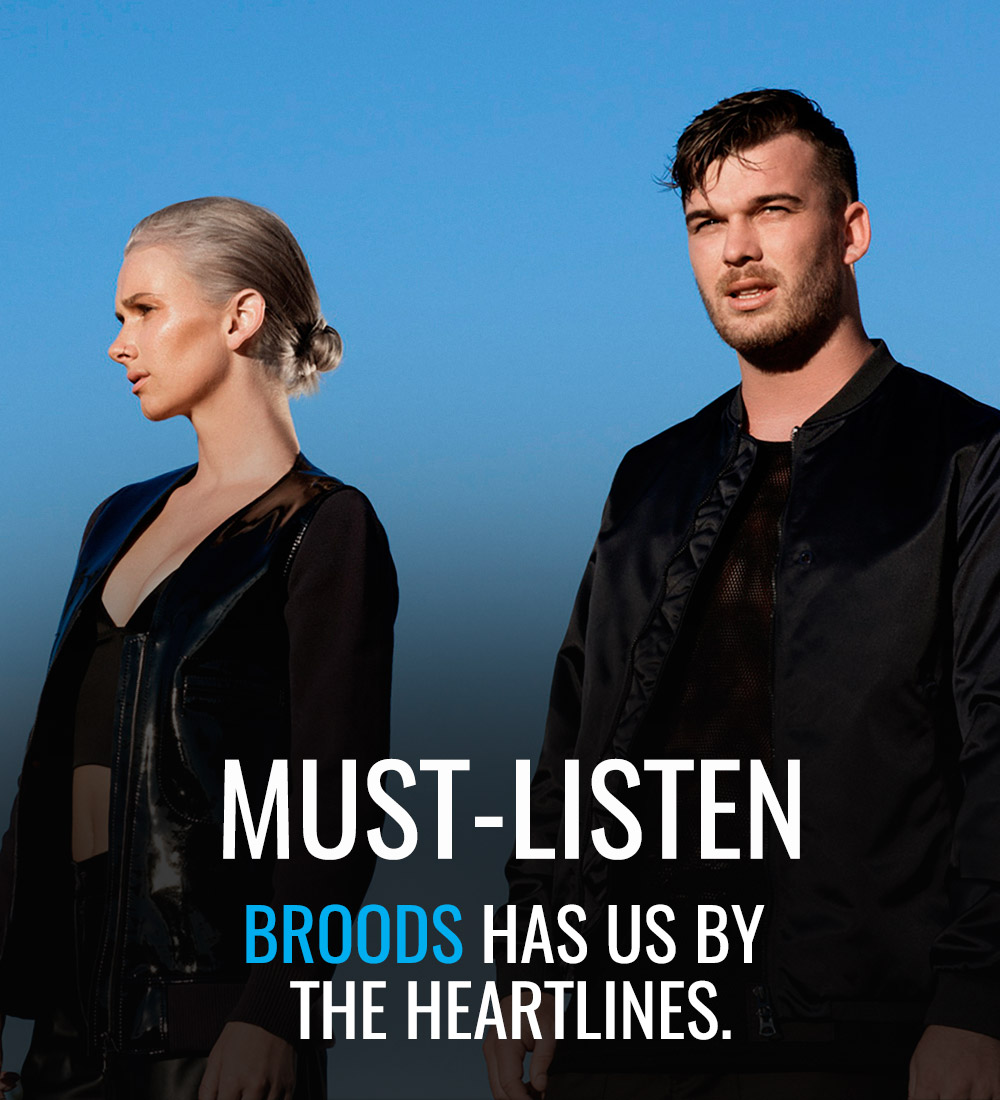

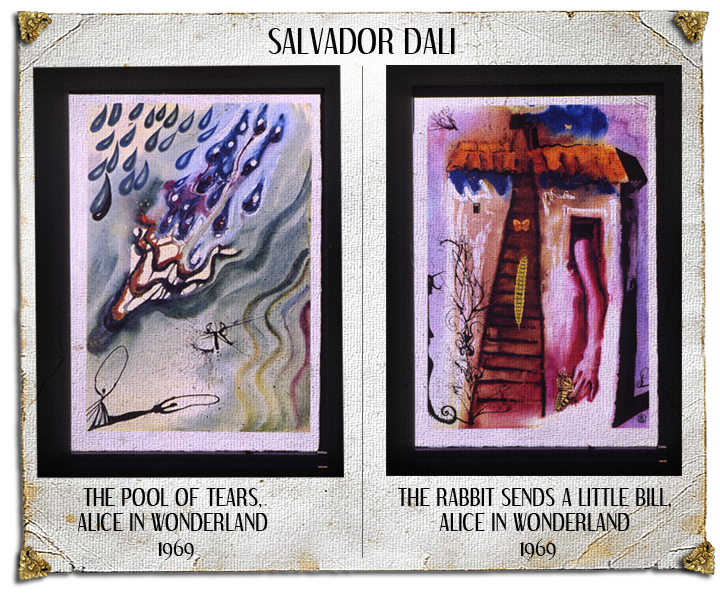

The exhibition showcases these influences with pieces by Surrealist artists, including Salvador Dali, from the 1930s onwards, who were drawn to the fantastical world of Wonderland. Conceptual artists of the ’60s and ’70s pop art culture were drawn to the language of Alice in Wonderland and its relationship to perception.

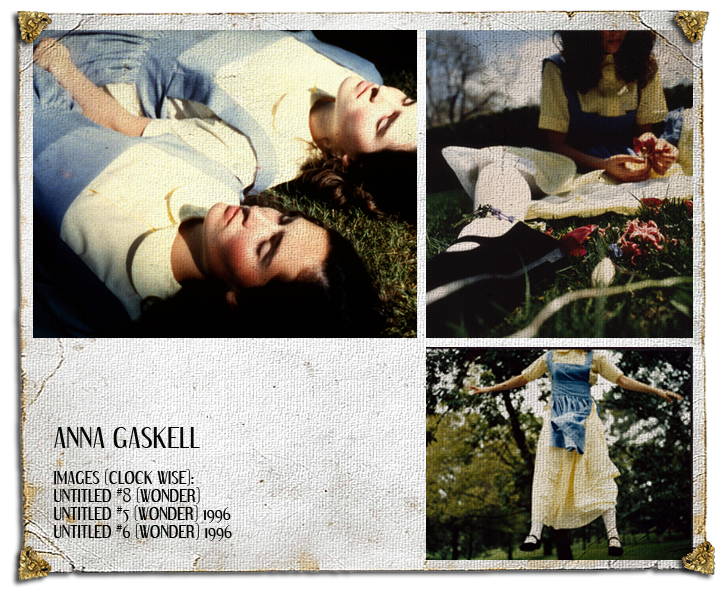

The exhibition also delves into contemporary art, demonstrating the continuing artistic relevance of the idea of the journey from childhood to adulthood, language, meaning and nonsense, scale and perspective, and perception and reality. Contemporary artists Liliana Porter and Samantha Sweeting took a moment to talk to FILLER.

Wonderland Wanderings: Liliana Porter

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has never been out of print. What is it about Lewis Carroll’s original story that allows it to remain so widely popular and able to survive generation after generation?

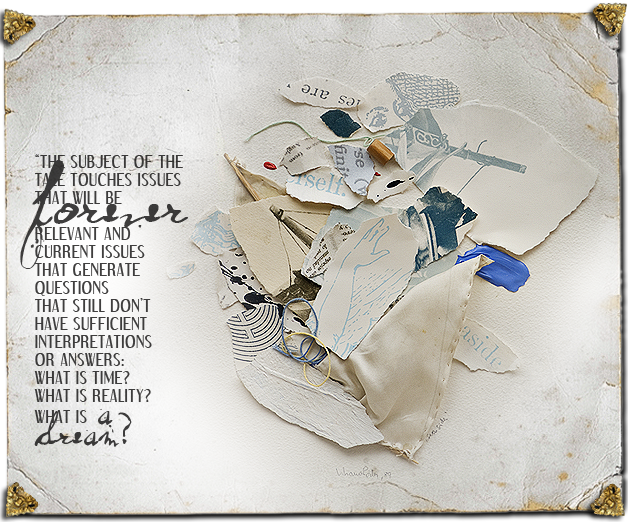

The subject of the tale touches issues that will be forever relevant and current, issues that generate questions that still don’t have sufficient interpretations or answers: What is time? What is reality? What is really a dream?

What narrative themes did you draw upon from the classic story when referencing it in your own work?

For my own work, specifically in some etchings and silkscreens, I have used the image of the book opened on “The Pool of Tears” chapter. In addition, I appropriated the image of the rabbit and also of Alice drowning in her own tears for wall installations, paintings and works on paper. I remember also a dialogue I created in 1997 between a plaster Alice’s rabbit that I bought at the Metropolitan Museum in New York and a very odd image of Che Guevara made in some kind of painted rubber. I photographed and framed the Che impersonation . Then the plaster rabbit was placed standing on a shelf that was attached outside the photograph. They seem to communicate very well regardless of differences in time, physicality and circumstances. I am interested in those kinds of “improbable encounters.”

There have been many variations or movements in the telling of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland throughout the years. This cultural phenomenon is apparent in the different pieces in the show spread across all artistic mediums. How does a modern piece of artwork such as yours re-contextualize and modernize the original story and does this challenge the audience’s perspective of the familiar narrative?

The way I used the images of Alice in my own work did not change the original concept of the tale. It is the tale that enriches my own narrative.

The phrase “down the rabbit hole” — a metaphor for adventure into the unknown — had become a colloquial term in modern day language often associated with a psychedelic experience. What does the “rabbit hole” represent in your own head?

It represents, as you stated, the adventure into the unknown or into alternative ways of perception.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a coming-of-age story: a document of the journey from childhood to adulthood. Are there elements of your own coming-of- age intertwined with your reinterpretation of Carroll’s narrative?

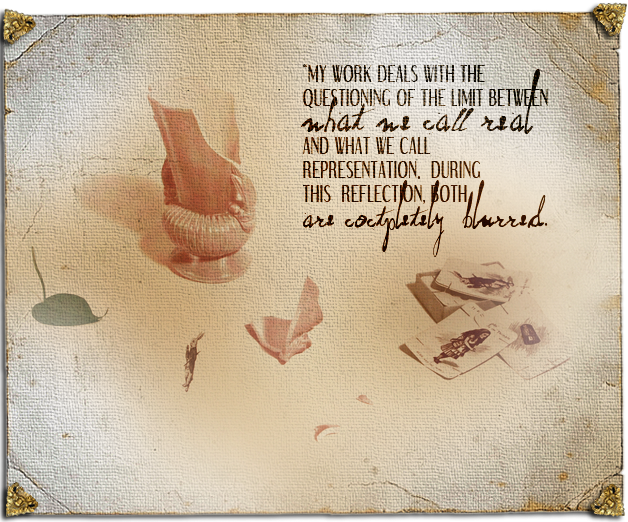

My work deals with the questioning of the limit between what we call real and what we call representation. During this reflexion, both perceptions (coming from childhood or adulthood ) are completely blurred.

How do the surreal or nonsensical aspects of Carroll’s story play out in your art, including themes such as scale/perspective, language and socio-cultural tradition?

I feel very identified with Carroll’s story in many aspects: the questioning of the limit between the nonsensical and the rational and the way that it is very easy to reverse apparent logical thinking into meaningless territory.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has multiple levels of meaning to its readers: to a young child it reads like a fantasy, while to an older reader there are lessons layered through the text. When did you first read Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and what did it mean to you?

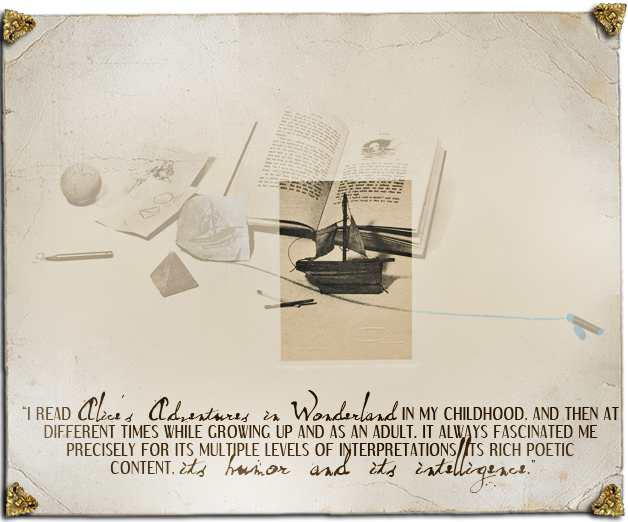

I read Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in my childhood and then at different times while growing up and as an adult. It always fascinated me precisely for its multiple levels of interpretations, its rich poetic content, its humour and its intelligence. Also, it is important to me the play with the concept of time, a subject that always intrigues me and it is present in my own work.

Who is your favourite character in the story and why?

I don’t have a favourite.

The story is a very visual one. It’s apparent Lewis Carroll found it important to incorporate images in with his text. How does the author’s pictorial imaginings effect the audience’s interpretation of the story? What about it influenced your own work?

John Tenniel’s illustrations are the ones that I have in my mind when I visualize the characters, to the point that if a I see a book illustrated by anybody else I don’t like it at all.

A common theme demonstrated through art and adaptations of Carroll’s narrative is the sexuality of a young Alice. Why do you think this is so popular a theme and does your work also touch upon this subject?

My work does not touch upon the subject of the sexuality of young Alice. Sexuality is always a popular theme, I guess.