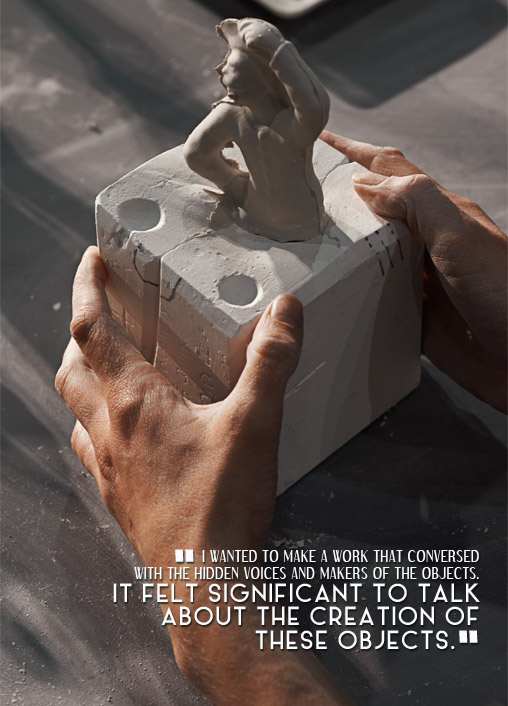

Sat before an army of miniature figurines, their shadows blanketing the floor, Clare Twomey ignores the camera as she works her fingers—white with dusty residue—around a raw brick of clay. It’s clear: this—the worktable, the clay, the figurines—this is the artist’s native habitat.

In a career first, the British ceramic artist—who boasts exhibits at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, the Tate Gallery in Liverpool, and Kyoto’s Museum of Modern Art—has transported her “studio” across the pond to Canada to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Toronto’s Gardiner Museum, with a performative installation.

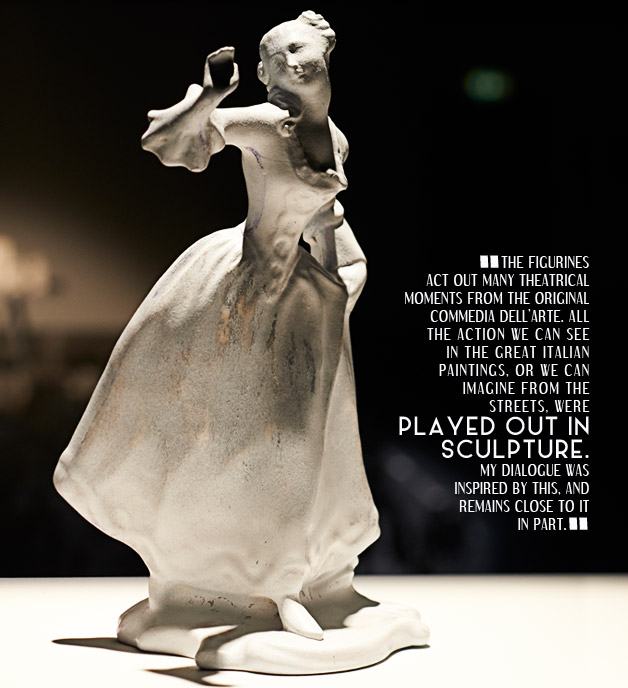

Aptly entitled, “Piece by Piece,” the exhibit engages in an ambitious dialogue with the past, mediated by the Gardiner’s own rare Commedia dell’Arte Harlequin collection. While the artist had innumerable sources of inspiration to tap into at Canada’s national ceramics museum, for Twomey, the choice to dedicate the anniversary project to this particular collection of porcelain figurines seemed to be determined by the figurines themselves.

“I felt they had a story to tell and these silent voices had an opportunity to be gathered,” explains the artist. “I wanted to make a work that conversed with the hidden voices and makers of the objects. I talk often of the need of the heroic work of the collectors to be placed in public view for all to see, but in this work, it felt significant to talk about the creation of these objects.”

To describe “Piece by Piece” as a large-scale installation, doesn’t do justice to the immense scope of Twomey’s exhibit. Encompassing over 2,000 unique ceramic figurines, “Piece by Piece” has garnered critical acclaim since opening last month with a live, on-site viewing of the artist herself at work, creating additional statuettes. On display through till January 4th, visitors are invited to explore Twomey’s haunting world, and stand in awe of how the artist has traveled back in time to unmasked the Commedia dell’Arte Harlequin era and unfurled 18th century life, laying bare the glory, the hardships and swivel of emotions marking the age.

“The work I made is a love song to the wonder of the Gardiner’s Commedia dell’Arte Harlequin collection, and the great task of the collectors to form its dialogues and textures,” says Twomey of the exhibit.

An artist with an obvious talent for creating enchanted and evocative worlds from a simple brick of clay, we were eager to speak with Twomey about her creative process and the inspiration behind her artistic vision. Below, the artist takes FILLER through her premiere Canadian exhibit and explains how history is a thing of beautiful drama, just waiting to be moulded.

What about the museum’s Commedia dell’Arte Harlequin collection originally caught your attention and inspired your latest exhibition?

I was inspired by the story of how the wonderful Helen and George Gardiner collected, as it was George’s special delight. Commedia dell’Arte defines the centre of the Gardiner Museum so completely—the finesse of the figurines, the silent plays acted out and the activities of the figurines held within these delicate cases of glass.

You must be excited to be a part of the museum’s 30th anniversary celebration. Did you feel any pressure preparing the sculptures knowing that they would be a major part of commemorating the milestone?

I only felt excitement; to be trusted is such an honor. I felt no pressure, as the support from the Gardiner Museum was remarkable.

Takes us through your creative process for “Piece by Piece,” from start to finish, how does a sculpture come to be?

My focus for the work was George Gardiner’s collection of figurines. I took just these figurines out of all of the wonderful objects in the museum. Of course there is the history of the Commedia dell’Arte—the street theatre of much humbler beginnings rising to these stars of making and craftsmanship.

And the theme?

So much more is released about other objects in the collection by displaying the exhibit in one area of the museum. I hope the release of dialogue about the making of these figurines leads the audience into further inquiry about how the other collections were made.

How did you explore this and make the connection?

The relationship was formed: the past in the form of the historic figurines; the present with the figurines on the floor just made; and the future by the maker who is continually making for three months. This concept of a dialogue between these three parts of the sculpture helps the viewer to float between the fixed histories of the museum and its relationship to the continuum of making that is present and continual.

Practically, take me through your process.

On a more practical note, I selected figurines from the collection, which were then 3D scanned in Toronto. These were emailed to my studio in London where we had the scans printed and reproduced for mould making to make 2,000 figurines in ten days.

How was your visit to Toronto back in the Fall?

When I arrived in Toronto, I spent days working on the floor areas while the historic figures were placed in their lofty vitrines and the handsome table was placed at the opposite point in the room. The makers who are continuing to make the work carried on what I had passed on to them, which was the form of the slow dance of making the figurines with the hope of creating a perfect piece to place in the historic collection.

That sounds incredible. I understand that the exhibit features 2,000 ceramic figurines that explore themes of war and peace, love and hate, death and destruction, and victory and defeat. Is there one subject out of the group that you were particularly interested in exploring?

The figurines act out many theatrical moments from the original Commedia dell’Arte. All the action we can see in the great Italian paintings or we can imagine from the streets were played out in sculpture. My dialogue was inspired by this and remains close to it in part. Other actions are that of the studio practice, figures lined up for inspection—are they good enough to be accepted?

2,000 ceramic figurines is quite a lot, it must have been quite daunting to complete this project, no? Did you ever feel overwhelmed?

I enjoy making challenging work; I created tens of thousands of pieces for Cape Farewell at the Eden project and other thousands across other international museums. I had a great team working with me and we were full of skill so the fabrication was an exciting and galvanizing time, as we made the work by hand “piece by piece” in London.

Each piece in the new collection is a document of history, has history always been something that you’ve been inspired to incorporate into your art?

I am interested in how we relate to history and how we navigate history as past when it may also be present. Working with history again and again only led me to the contemporary, and being able to discuss both of those co–existing states, past and present, is central to much of my work. Being the voice that creates bridges and continuums that relate to our lives today is vital in my work and to museums and other institutes.

You can really perceive your efforts to create those bridges in your work. The word “enchanted” has been used to describe “Piece by Piece;” is the whimsical a popular theme in your work, and how have you harnessed it through these new sculptures?

Whimsical implies something with less weight and enchanted implies something that is less real. The real belongs to the viewer, who enters the exhibition space at the Gardiner Museum, and starts a journey with the work I have made and it’s impossible to remain other as the door closes behind you and the dim lights of the gallery draw you to its center.

I mentioned how others have described your new collection, how would you sum it up?

“Piece by Piece” is a live work that breathes the contemporary into history by its tension of continual making and dialogue with the hierarchy of the museum and the perfection of the objects within.

I like that description. What originally drew you to ceramics?

I was drawn into ceramics because of its ability to be formed, its commonality and its friendship in encounter.

Are there any other mediums outside of clay that you would like to expand into, or is it important to you to stay focused on just one?

The main mediums I work with alongside clay are people, institutes and communities. The Gardiner Museum has been changed by this work, as have so many other museums that I have worked with. I ask a great deal from curatorial teams, from modifying the normal running of the museum to altering space to accommodate more. This is all difficult to achieve—to ask an institution to think again about what they do and how they do it—and it is brave of the institutes to welcome the idea in. It’s astounding to see how much can be achieved in the forming of the new, not only in material terms, but new in the sense of community, audience and actions.

The exhibit currently on at The Gardiner is most definitely “new” in that regard. What was it like working on sculptures in front of an audience during the press preview? I imagine it must have been slightly intimidating having an audience watch you so closely during the creative process.

I have worked with Siobhan Davies, the acclaimed British choreographer for the past four years, to understand the role of the performative space, what it means to use that space and to allow tension to play into the work. The work paces this out and it’s a wild and stimulating thing to create. I felt very honored to be in the frame of the work and seeing two years work coming to life.

What about your actual studio space, what’s that like?

My studio space is full of work. The studio is in a very urban place tucked in behind the streets of the Tate Modern Gallery by the Thames. The work is lined up around the library end of the studio and reminds me of the thoughts that have led to the challenge I am facing now, whatever that might be. It reminds me to be brave enough to try again. There is a workshop end to the studio that is bright and clean and waiting to be used.

That sounds like an incredible space, with all the work filling it up.

A lot of the works in progress sit in marquette form; they are waiting to be developed. There are samples of works that are in progress and there are sketchbooks full of notes slowly developing.

What’s next for you, are you working on any new projects?

The York Museum in the UK is reopening after its £8 million refurbishment, and I’m working on a central piece that will fill the historic building from its entrance to its roof. The work will be formed of 10,000 handmade bowls that bring together a new community in six months to make and discuss the acts of making.

Anything else? Though that sounds like a project that will keep you busy enough!

I am also working with the Holocaust Memorial Day trust to create a work that enables thinking and discussion. Beyond that I am working into 2016 with the Bronte Museum in the UK, as well as the Crafts Council, UK and the National Museum of Wales. In North America, I will be exhibiting a work at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in 2015.