It’s a city where small town nobodies flock to become Hollywood somebodies, a city where stars from the big screen win public office, a city where one of the best nights outs is found in an oversized mansion populated by magicians — it’s a city of angeles and home to Miley Cyrus; this is Los Angeles, California.

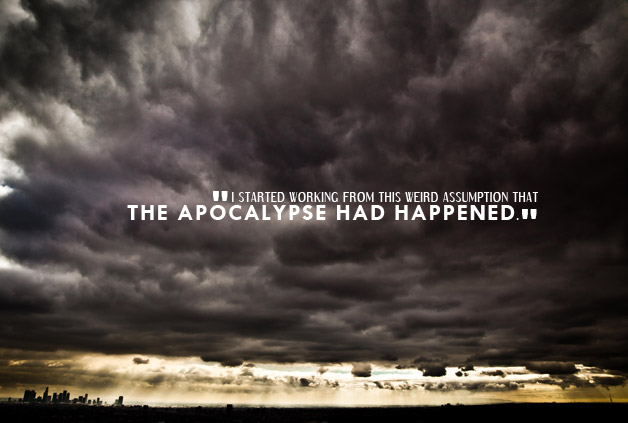

Considering L.A.’s flair for drama, it’s fitting that the metropolis should play home base to the world’s first post-apocalyptic cult. Oh, you didn’t hear? The Mayan Apocalypse happened back in December 21, 2012…just no one bothered to notice.

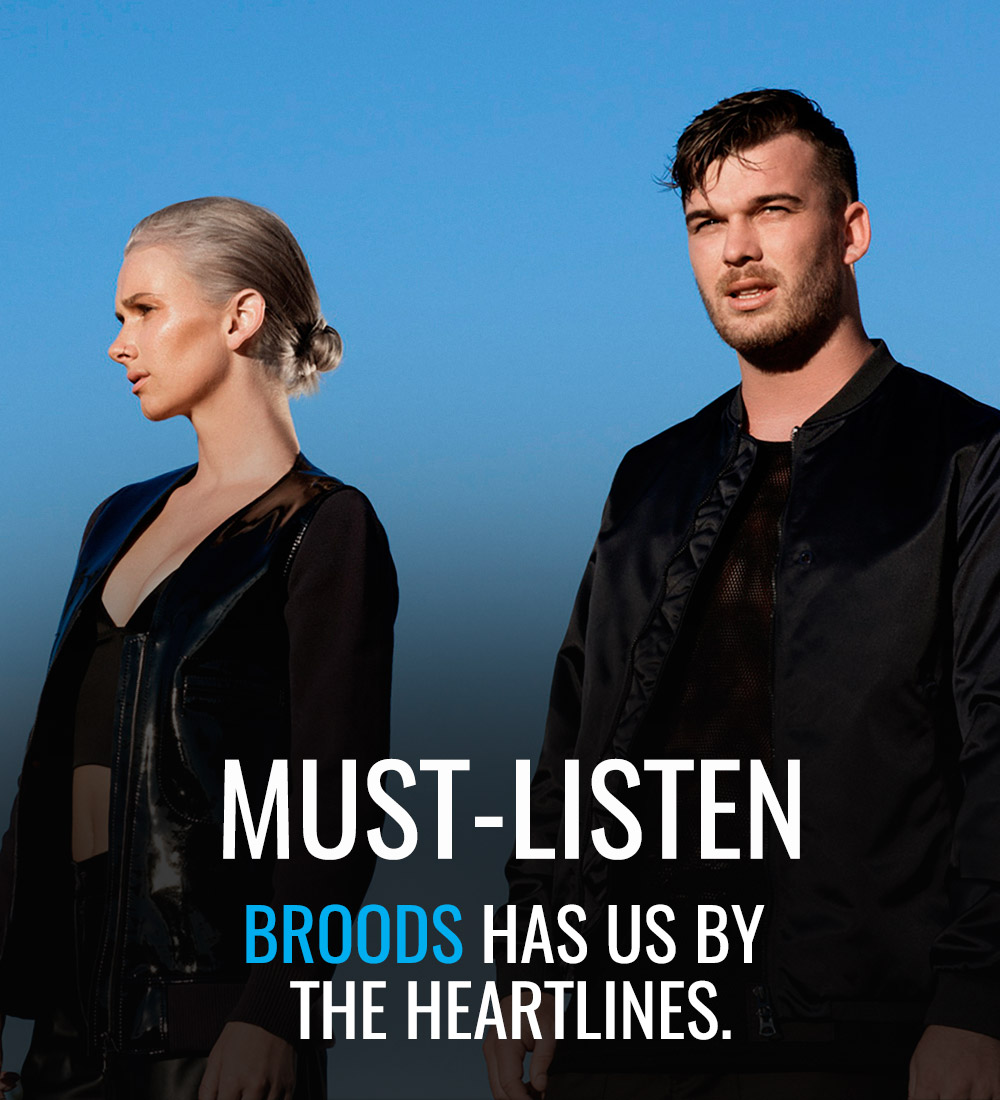

Or so hypothesizes Moby in his latest photography exhibit, Innocents, in which the acclaimed musician imagines a post-apocalyptic Los Angeles, where residents hide their shame for humanity’s role in the end, behind rubber animal masks, bed sheets and allegiance to the “Cult of Innocents.”

“I started thinking of it in terms of turning an ocean liner…” explains Moby during our phone interview. “I’ve never driven an ocean liner, but I assume that when you turn an ocean liner, you spin the wheel and it sometimes takes a really long time before you even realize the ocean liner has changed trajectory. Then I started thinking about something as big as our planet, and if there was an apocalypse, maybe it’s a very gradual apocalypse.”

His third photography exhibit, Innocents — on display at the Project Gallery in Los Angeles until March 28th — marks a departure from the rockumentary style that garnered critical acclaimed for the artist’s first exhibition, Destroyed, held in New York City, 2011. “Those were more reportage and this is more creation,” affirms Moby.

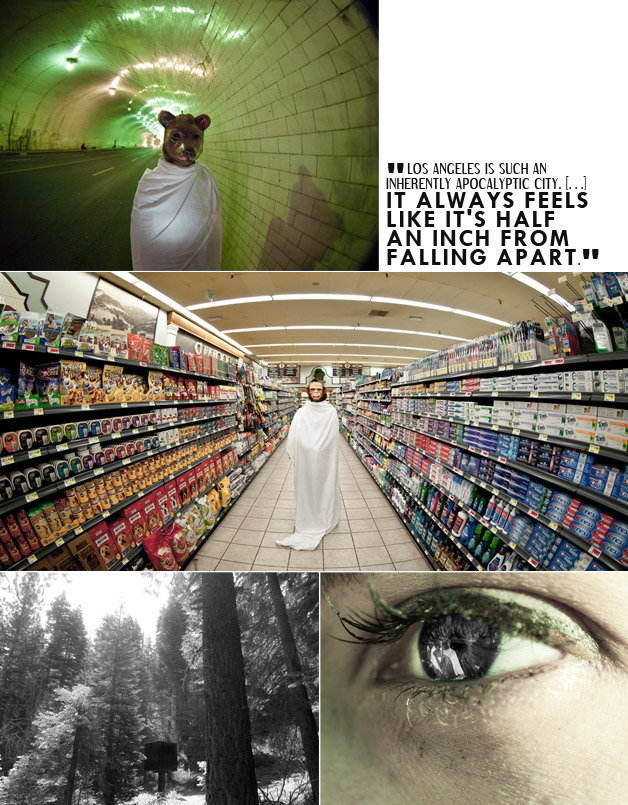

With his latest collection of photography, Moby takes control of the image and superimposes fiction onto reality, entrusting the ensuing narrative with the viewer to decipher. “It creates this almost kind of cognitive disbelief,” he says of the exhibit’s stranger-than-fiction-scenes. “Like someone in a monkey mask in a sheet, that’s strange, our brains don’t know how to process that, but when you enter that into a very familiar environment, I think that cognitively it can be a really interesting thing.”

As for the backdrop, according to Moby, Los Angeles, cults and the apocalypse go hand-in-hand, it’s a simple matter of geography. “I really feel like Los Angeles is such an inherently apocalyptic city,” he explains. “Like some places — Toronto, New York, San Francisco, Milan, Sydney — feel very stable. You feel like the city really knows what they’re doing — it feels solid, it feels stable. But when you’re in L.A., it always feels like it’s half an inch from falling apart.”

Traversing the bleak, while documenting the beautiful, Innocents is a playful glimpse at the “present” society likes to call the future. Below, we talk to Moby about hatching the apocalypse, the fashion of cults and ritual reinvention in the age of social media.

Can you explain the story behind the Innocents exhibit?

The idea behind the show…trying to figure out where to start…do you remember a couple of years ago, there was all this talk of the Mayan Apocalypse?

I remember that.

People were assuming that on December 21, 2012, the apocalypse was going to happen, and the world would be forever changed and altered. And then December 21, 2012 happened, and there was no real evidence that anything had happened, that any dramatic shift had taken place. And I don’t think a lot of people really believed it was going to happen, but I think some of my New Age hippie friends were disappointed.

Yeah, I knew a few of those types too.

So, I started thinking, what if the Mayan Apocalypse has happened? Then I started working from this weird assumption that the apocalypse had happened…and trying to collect evidence supporting this idea. It’s almost separate from the art show, but I think you can make a pretty compelling case that the world is so different now even than twenty or thirty years ago.

Yes, that’s definitely true.

It seems like there has been a huge shift in the word, but we don’t necessarily notice it because we deal with it day in, day out. So that’s the basic premise of the show, that the apocalypse has happened…and…I’m a little obsessed with cults, especially since I moved to L.A. — L.A. is kind of ground zero for cults.

And this is where the group of masked people come in?

Yeah, and if you look at the last few thousand years, there have been lots and lots of cults — some benign, some malignant — but one of things all the cults have in common is they all sort of believe that they’re the ones that are equipped to deal with the impending apocalypse.

Yeah, that they’ll be the sole survivors and you should follow them.

Yeah. And I thought it would be interesting to say, what if the apocalypse had already happened, and what if this fake cult was the world’s first post-apocalyptic cult; what would a post apocalyptic cult look like? So all that is kind of the premise of the show. And then, I guess the third component is the value we give certain semiotic signifiers. I think it’s really interesting…the meaning and the value that we ascribe to things collectively, usually just based on context and an almost agreed upon meaning.

You really get a sense of the city, Los Angeles, from your images. And I like the way the scenes of nature are set alongside photos of your post-apocalyptic cult.

With most cities, nature is really kept at bay, whereas L.A. to the west you have the gigantic Pacific Ocean; and to the east, you have the vast desert that doesn’t support human life; and then running right though the middle of the city, you have a giant mountain range, which has a million acres of undeveloped land filled with mountain lions and bears. So there’s this very strange relationship with a balance between the human world and the ancient uncaring natural world. That’s another element…another element of the show is looking at an apocalypse that to an extent reframes the human relationship with the ancient natural world…if that makes any sense.

It definitely does. And how do the masks play into your apocalyptic scenes, are they meant to distance humanity and add a surreal element to the photos?

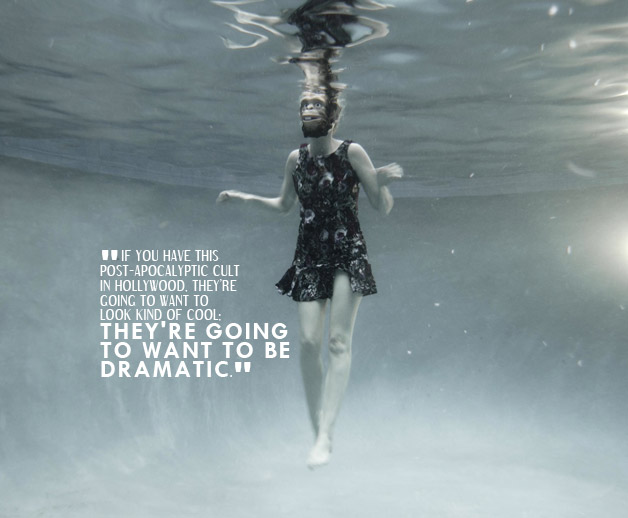

Well, I was thinking, if you have this post-apocalyptic cult in Hollywood, they’re going to want to look kinda cool — they’re going to want to be dramatic. And this “Cult of Innocents,” they’re basically concealing themselves with masks and sheets because of shame.

Shame for what?

They’re looking at the last few thousand years of human behaviour and their response to that is to conceal themselves because their expressing their shame at humanity…and trying to look cool in the process.

And what are some of the rituals that the exhibit is fleshing out or commenting on? For example, you see the person in the monkey mask in the aisle of a grocery store, which I find really interesting.

Well, part of it is just leaving things ambiguous. With photography, I like the idea of introducing ideas, but ultimately letting things remain open to interpretation. If I go to an art show or a photo show, and I feel like the artist is too aggressively leading me to a conclusion, I resent them for it. I really feel like the viewer should be presented with relatively ambiguous information and make up their own minds. Like the figure in a monkey mask, you don’t know if it’s real, you don’t know if it’s malicious or benign, you don’t know if it’s supernatural.

It makes you question what exactly is going on. And, in terms of ritual, was reinvention something you were looking at too? Los Angeles is after all known as the place to go to reinvent oneself.

It’s funny, I was in this diner the other day, and on the wall they had all these pictures of well-known movie stars, everyone from Marilyn Monroe to Grace Kelly, and I was looking at them and I was actually thinking about this idea of reinvention. Like, we all know that Marilyn Monroe was essentially a well-intentioned white trash girl — we all know that — but we all choose to believe that she was a glamorous movie star…even though she didn’t even believe that she was a glamourous movie star.

That’s true. It’s the audience that believed in that image.

It’s belief in the image, even though we know it’s not true. We love putting our critical facilities on hold and believing a better story…that’s really L.A.’s defining characteristic, people coming here and playing on this idea — the reinvention is a ruse, but everyone very happily buys into it.

Social media has sort of allowed everyone to get in on the ruse of reinvention. Now we all can create what seems like a more glamourous life — essentially we can lie.

That’s actually one of the main reasons why I joined Facebook. I have my professional Facebook account, but I also have my personal Facebook account, and my favourite things about it is seeing how people choose to present themselves. Like when someone chooses their profile picture, I find it so endearing. Like say if my friend, let’s say Jennie, puts up a new profile picture, everyone who’s seen this profile picture, knows what Jennie looks like, but Jennie will still put up a very glamourized picture, even though everyone knows exactly what she looks like. And the whole process of really finding the idealized version of themselves, and then putting it up as a representation of themselves to people who already know what they look like…I find it so utterly endearing. And I don’t mean it in a patronizing way, I do the same thing, but I find it fascinating. Basically that’s all I do on Facebook, is see who’s changing their profile and imagining what led them to make that choice.

Do you see social media — Facebook, Twitter, Instagram — is it a cult of its own?

I guess so…I want to say yes, and it is, but it doesn’t behave like a more traditional cult. Certainly things like Twitter and Instagram have cult-like elements, there’s definitely a sense of joining and belonging…maybe it’s like a newer type of cult, where there is no authority, but everyone happily gives up their will to be a part of it.

Are you a part of it?

Oh, yeah. It’s all neurochemical. If I sit down with my phone, and I haven’t been on Instagram for a while and I click on it, you can almost feel the serotonin…but it doesn’t last very long.

Okay, back to the exhibit. How do you think your evolution as a photographer reveals itself in Innocents, specifically in comparison to your first photography exhibit Destroyed?

So, I’ve had three photo shows now, the first, Destroyed, was about the weirdness of going on tour, and living in airport and hotels, and I had a show in L.A. a couple of years ago, that didn’t really have a name, but it was all pictures of crowds, and I guess this exhibition is different because it has nothing to do with my professional life. I’m not documenting anything.

I imagine you come across a diversity of photo ops on tour, as Destroyed demonstrated.

I love the spontaneity of it, but there’s always a part of me that feels like a little bit like a fraud if I’m just putting up snap shots — there’s not much craft. I guess I do like intentionality and control of a more manual camera…but it doesn’t mean that just because I’m controlling the variables, it makes it better. Sometimes a quick snap shot can be the best possible picture. Just look at someone like André Kertész, he was sort of the master of that.

You mention intentionality and control, in terms of the narrative do you find sometimes it can develop on its own? After you’ve finished taking the photos, is the narrative not always what you intended it to be?

Oh, yeah. Often times the narrative presents itself later, or the narrative is created just by random assembly. I really like the idea of not controlling the process too much, almost letting your intuition be your guide. And also, not having to come up with something that is a rock solid cohesive narrative.

It leaves the viewer with more to think about I think. I understand you were working on this exhibit at the same time as your most recent album of the same name. Did you draw inspiration from the same place for the both?

They’re both made in L.A. and they’re both really inspired by the strangeness of Los Angeles, but in a way, the music and the imagery do very different things. The imagery is very much about the strangeness of life in a huge dysfunctional city, and the music is actually softer and provincial. The music reflects the quieter, gentler suburban quality of L.A., and the imagery, the art, reflects the more apocalyptic, disconcerning aspects of L.A.

It would be interesting to look at the photos, while listening to the album at the same time.

Yeah, I don’t know…I wonder if it would make sense…