Industry professionals are waking up and shaking it up at the Anti Design Festival (ADF) in London. Claiming to take the hammer to the comatose, pampered VIP festival production model adopted by their counterpart — the London Design Festival — the ADF manifesto makes the urgent promise to “unlock creative fires and ideas in defiance of generic culture and art as entertainment” and explore “spaces hitherto deemed out-of-bounds by a purely commercial criteria.” Directed by world renowned graphic designer Neville Brody, the Anti Design Festival is fighting to bring back danger, glorify risk, and offer a platform for honest, dirty, and raw design as a means of interrogating the world we live in today, and proposing creative solutions to achieve the one we want to live in tomorrow.

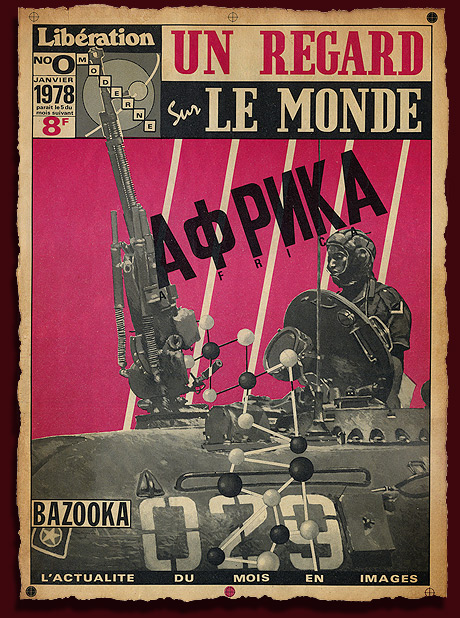

Un Regard sur le Monde cover, loulou picasso 1978.

Hark, does this smell of Revolution? Anarchy? Maybe. But that brings us to an important question, “Which is more dangerous: industry terrorism or the lack thereof ?” One good way to answer this question is to take a look back in history. Which is precisely why the infamous guerrilla design group Bazooka was asked to join forces with artist-curator Stuart Semple to mount the headlining exhibition during the festival.

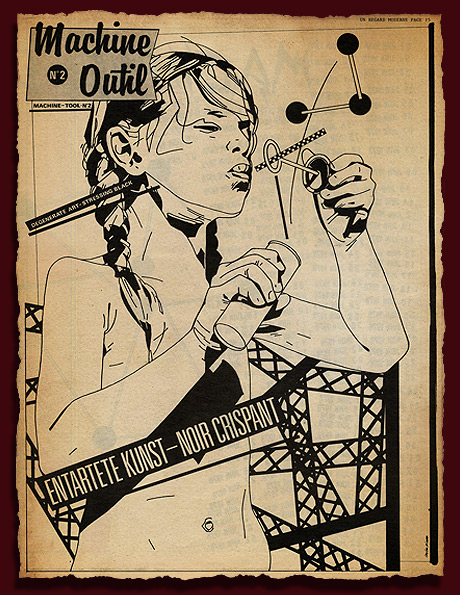

L'art j'y crois, in l'Echo des Savanes n°34, Kiki Picasso 1979.

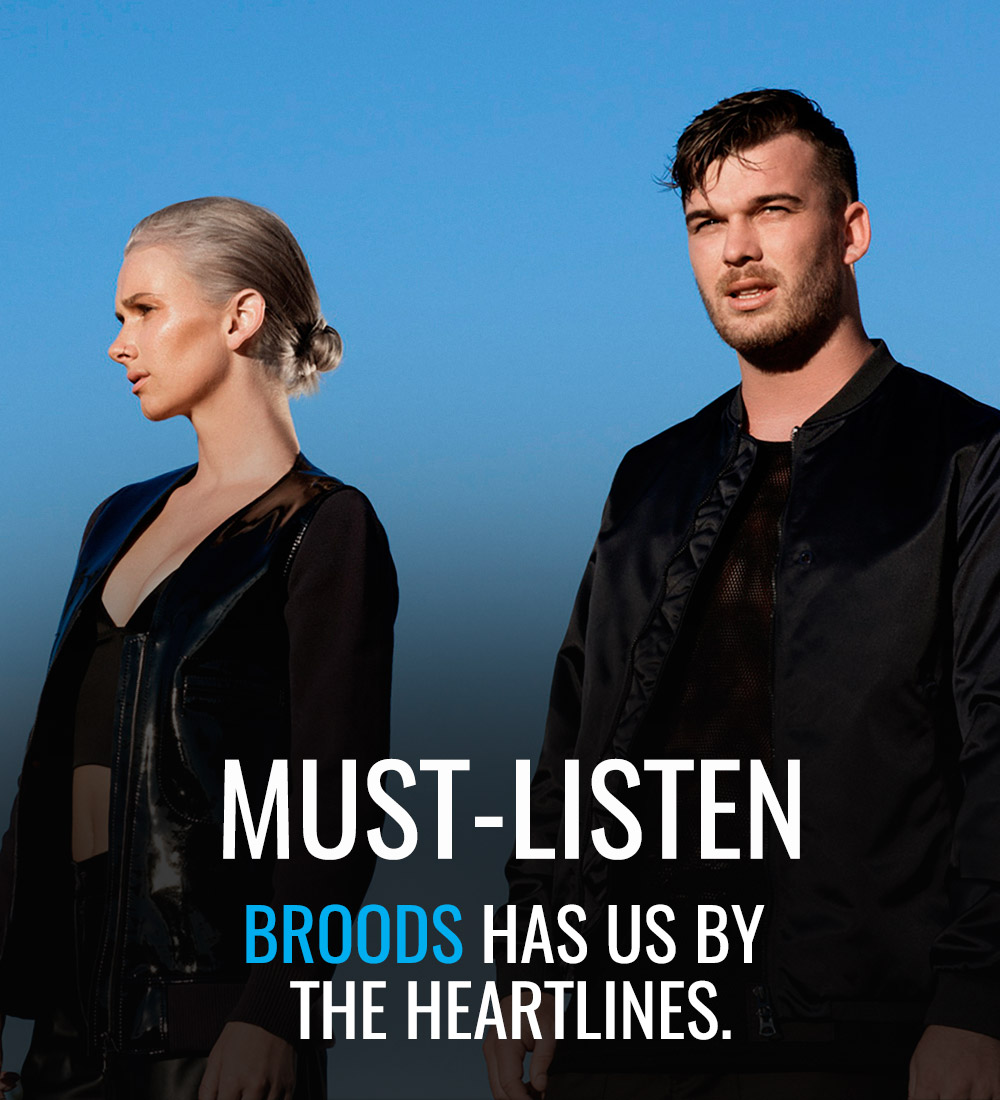

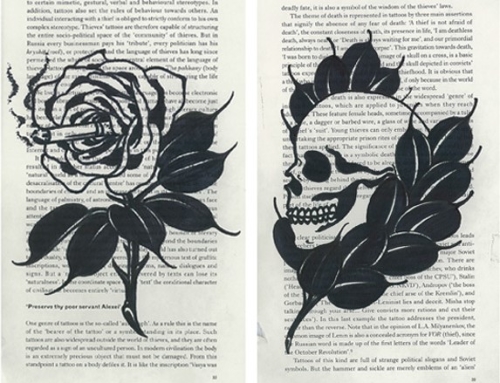

The Paris-based group of designers Bazooka, initially established in 1974, is renowned for their commando and guerrilla design assaults on different forms of mass media. The group, comprised of a handful of students in the French fine arts schools, first gained notoriety in ’77 while commissioned to do design work for the famous left-wing French newspaper Liberation. True to their namesake, they opted to “y foutre la merde” (wreak havoc there) by publishing designs that re-appropriated media images and used them to interrogate the values of consumer culture. Their “punk” attitude got them swiftly kicked off the job but Liberation did nonetheless ask them to publish a satellite magazine called Un regard modern (A modern view), equally short-lived. In parallel, Bazooka edited fanzines, comics, vinyl covers, and later video work, much of which will be on show at the Aubin gallery and cinema for the Anti Design Festival.

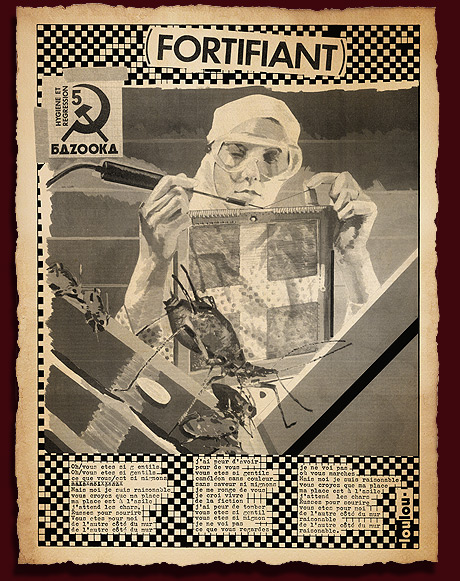

Loulou picasso, Un Regard Moderne n°4, 1978.

Acclaimed artist Stuart Semple will be curating the exhibition, Bazooka’s first in the U.K. Semple himself is known to appropriate, modify, and recontextualize icons, logos, slogans, and other consumer media images, underlining or glorifying their inherent fallacies, which assures a particularly interesting relecture of Bazooka’s vast archives of print and video work.

Kiki Picasso and Loulou Picasso, two of the founding fathers of Bazooka, will be representing the group during the ADF. In an exclusive interview for Filler Magazine, Loulou shares his thoughts on the ADF, Aubin, and the importance of acting out of line.

What is your favourite logo? Commercial?

If Bazooka had written a manifesto in the 70s, how closely would it resemble that of the ADF ?

Bazooka is a group. We spent our time drawing. It never occurred to us to theorize about our work. Nor did we collaborate in hopes of explaining the “graphic resistance.” We just wanted to be modern. To be modern means to be capable of mixing two existing ideas to give birth to new ones. One cannot be modern without being cultivated (regardless of what that “culture” is). And rules are made to be broken.

That sounds rebellious.

Change never comes from good students, fundamentalists, nor believers in this or that system. Change is the birthchild of miscreants, of people “impregnated” by doubt. The younger generation has taken refuge in growing in complete safety, in too many ‘chapels’ that only the experts are able to name. Too few dare to seek a global vision of society. The protests are silent and icons anorexic. There is no future in that. The arrival of change is always joyous and full of life. The Revolution cannot be sad.

That’s pretty close to the ADF, no?

How does the culture=money equation fit into your own career?

I have a mental construct that places art above all, and I live in a society that recently placed the economy above all. This can only be experienced badly! I’m poor.

Do you think the industry mistakes gross income with talent?

The renown of an artist today is not built on his work in and of itself, but on its business potential — its financial viability, potential for creating partnerships, having various subcontractors, communication. An artist’s career today is like managing a company. Few regard the quality, though many are fascinated by the increase in value.

It is very difficult these days to be a “painter;” being just a painter, working for free, is looked down upon.

Loulou picasso, acrylic, 2010.

Your art débuted in fanzines, why this medium?

We made our début by creating fanzines, even printing them ourselves to reduce the cost. Then we found alternative publishers. But this seemed insufficient and frustrating to me. Bazooka’s turning point idea was that of annexing territory, using the existing press as a field of experimentation, depicting the news from within this news media. I always follow the press to see how it evolves. An idea, an image, something that’s moving. A sign or omen pointing to the emergence of another world. An apparition.

Bazooka was established only a few years after the riots and social upheaval of ’68, how did Bazooka differ from other student groups protesting at the time?

We weren’t different. We were too young to actively participate in 1968. But we felt as though we belonged to a social group. Our adolescence wasn’t an archipelago of barren islands, but a real continent. Together we are stronger, that I quickly understood.

Political without an ideology. Activist without a doctrine. Bazooka was kind of like that.

You did eventually become a part of the larger movement though?

While we were working at the newspaper Liberation, we were at the heart of the movements of the far Left. It’s true that at the end of the 70s, violent and radical combat against capitalism flourished from a certain popularity. We spoke a lot about it, the stories were fascinating. We found therein the ideal romanticism of resistance and total engagement.

Were you close with Grapus, or other sociopolitical/culturally engaged student-run design groups in Paris at the time?

We’re still friends with the designers of our generation. The artists we love are our friends, our brothers. Those with whom we have produced, created, at one time or another.

Your use of collages of media images calls to mind video artist Edouard Sallier. Are there others you yourself see as following the Bazooka lineage?

I don’t want to know who adopts the “Bazooka” style these days. That doesn’t interest me. I am not interested by transmission, we know how that works. We see real clones, we copy much too much. Where is the transgression?

We are in a decadent, sad, and devout period, as history has already witnessed and managed to get rid of. Kiki and I continue to experiment with our collages. Or “mixing,” we should say. That is Bazooka’s invention.

Plan d'Urgence cover, in Engin Explosif Improvisé, Kiki et loulou picasso 2009.

How did your collaboration with Semple and the ADF come about?

We first met Neville Brody, who spoke to us about the ADF and of his intention to work with us. We were very pleased, and got to work quickly, as always. It wasn’t until later that we met Stuart. We are very pleased to be putting on the exhibition with him.

Similar to Bazooka, Semple’s work appropriates, revises, and consequently undermine or underline consumer values and ideas. I imagine the likeness in artistic vision made for a nice partnership.

This similarity creates a mutual understanding, which allows for a relaxed reflection while setting up this presentation.

If you had one phrase of warning to pass on to the next generation, what would it be?

“I go where others do not.” It is a sentence from our latest book, ENGIN EXPLOSIF IMPROVISÉ (Improvised Explosive Device), presented in the exhibition.

About the Author

Liz Bullen is an Artistic Director and painter. Originally from the east coast, she currently lives and works in Paris. She has done design work for notable institutions such as the Louvre Museum, The Science and Industry Museum in Paris, and the Accor Foundation. She is also the president of the collective “Transit Système” (www.transit-systeme.com), dedicated to the production and diffusion of contemporary art.

For more information on the Anti Design Festival, please visit: www.antidesignfestival.com or www.aubingallery.com/exhibition