A family’s dynamic is a living organism that feeds on memory. The trouble is, childhood drama is not always food for thought.

Director Nancy Savoca’s latest film Union Square imagines a pair of estranged sisters full up on the turbulence of their youth. In one corner is Lucy; played by Academy Award winner, Mira Sorvino, Lucy is a straight-talking, bold blonde with drama as plentiful as problems, and a spirit as free as her life is unraveled. In the other corner, a ruffled, withdrawn younger sister Jenny (Tammy Blanchard), who feigns a smile when the world is upside down, and whose upcoming nuptials represent her long awaited escape from the dysfunctional family that she’s worked to distant herself from for the better part of her adulthood. And then, big sister ends up at her front door with the intentions of making a fort out of her couch.

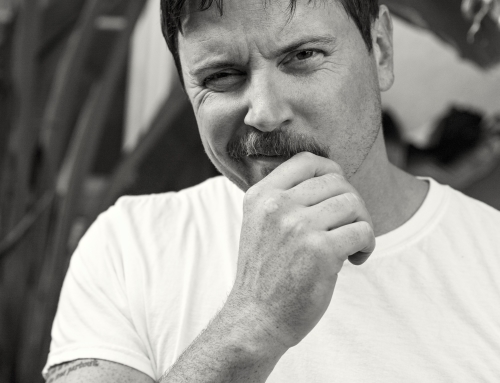

“That word dysfunctional is so funny,” says Savoca. “I don’t know which therapist came up with it because obviously we’ve all been functioning since the beginning of time, and I think that crazy people have existed since the beginning of time…so we’re doing a pretty good job functioning.” Savoca’s leading lady, Sorvino, agrees: “I don’t know if I ever met a completely functional one,” she says on the topic of families.

In our interview, Savoca and Sorvino interact like sisters themselves — functioning ones. Rather than straight individual answers, the two reply as one, finishing each others’ sentences, and chit chatting about their personal insights into the film while munching on chocolates.

When asked what inspired her to pen a story about rival siblings who are polar opposites, the director speaks to a comforting sense of familiarity inherent in the dysfunctional family storyline. “You get two people talking about their childhood, and you get two very different stories, and that fascinates me,” says Savoca. Sorvino adds with a straight face, but an obvious smile in her voice, “That’s why you have to have multiple children, so at least one of them will love you.”

The universality of the combustible, often fractured, nuclear family is a phenomenon that Savoca — who also co-wrote the script with Mary Tobler — dissects with exacting precision. Premiered at the 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, and in theatres now, Union Square tackles familial pains and grievances by way of comedy; gradually giving way to the evocative grip of the film’s plot.

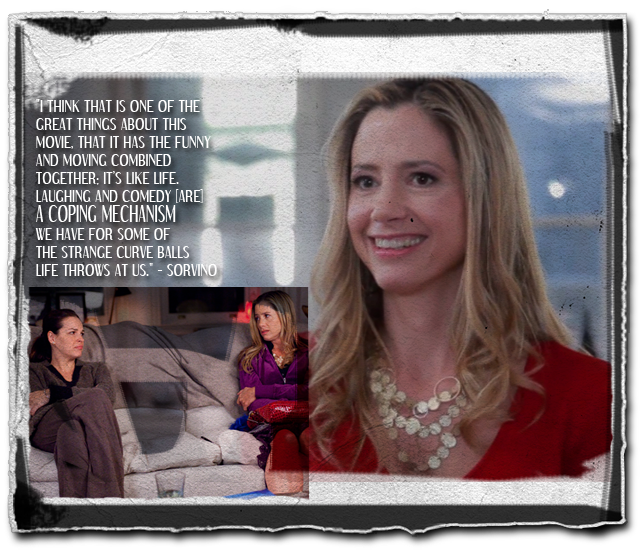

“I think that is one of the great things about this movie…that it has the funny and the moving combined together; it’s like life,” shares Sorvino. “Laughing and comedy is a coping mechanism we have for some of the strange curve balls life throws at us.”

Comparing the film to a Woody Allen dramedy — “something where you’re going to laugh and ponder and be moved — Sorvino’s admiration of her latest feature work derives from the film’s overall embodiment of quality indie-cinema. “[It’s] the best of what independent film can be, because it’s about human beings, and there are lots of secrets and lots of twists in it, but it doesn’t rely on car chases and special effects to achieve its cinematic power punch; it does it through real behavior, and great writing and directing.” Credit lies with Savoca — a pioneer in independent cinema — who takes the sting of reality and inserts it deep within the script, transforming clear-cut drama into a slice of life — a skill the director has been garnering acclaim for since her feature debut, True Love, which won the coveted Grand Jury Prize at the 1989 Sundance Film Festival.

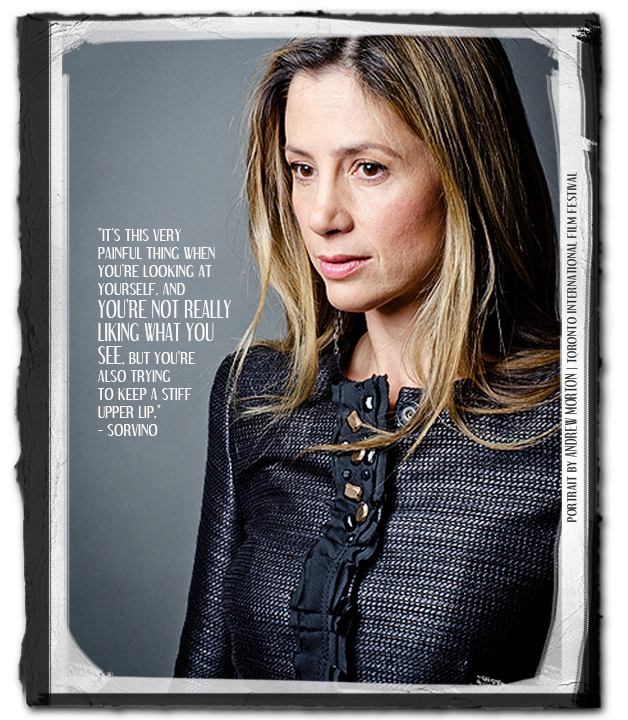

The drama in Union Square is humanized by its characters. When Sorvino’s Lucy is in the midst of a breakdown, it’s not her stream of tears that pinches the audience’s sense of self; it’s the moment when she looks up into the mirror — face wet from emotion — that speaks to us as real. “I love that moment, it’s so telling,” shares the director. As Savoca explains, it’s the genuine, almost adolescent self-consciousness that Lucy displays in this moment where she wants to see what she looks like crying, that convinced her to select the take.

“In my mind, I was so in that moment…so I guess I do that,” adds a laughing Sorvino on the subject. Savoca quickly counters: “Or Lucy possessing you does that.”

It’s precisely how Sorvino’s immerses herself into the story to become her character that actualizes the big emotional action of the Union Square script. “Writing it, I thought oh god, whoever is going to play this…how is this ever going to work,” confesses Savoca. “How do you have this whirlwind of a character [Lucy], and who’s playing opposite that character that just won’t melt into the wall and become a zero.”

It’s clear, casting was ranked Savoca’s greatest worry in the pre-production stages of Union Square, the key, according to her, to maintaining proportionate character development in the story. “I was super nervous about how this was going to work,” says the director. “When I found Mira and Tammy, I just said ‘thank you.’ Almost like I got a little lazy, like ‘oh good, let them do the work, I’m just going to watch.’” The feat was to find one actress, able to play the complex Lucy character so that she would be honest and revealing, and a second actress, who would be capable of assuming Jenny’s conflicted identity with an arresting authenticity.

Identity — as one fabricates it — is at the crux of the tension in Union Square. Mirrors play their part in each woman’s masquerade. While Jenny doesn’t have a mirror, Lucy lives in front of them. “She’s maintaining a façade that she rarely looks at because it’s not who she actually is, she’s not really comfortable in her own skin,” says Sorvino of Jenny. “My character has painted another kind of false face for herself — this oversexed hot little number. You see her trying on all her too-young-clothes at the bargain mart in the beginning [of the film], where she’s wearing that leopard top, and she’s looking at herself in the mirror, as she’s talking to her boyfriend who’s like rejecting her, and it’s this very painful thing when you’re looking at yourself, and you’re not really liking what you see, but you’re also trying to keep a stiff upper lip.”

In the role of sisters, Sorvino and Blanchard effortlessly ride the natural ebb and flow of sibling hostilities, rooted in unbreakable bonds, and the cool realization that family isn’t a tie that breaks with distance (or in Jenny and Lucy’s case, distancing), no matter how great the effort. The dichotomous rhythm between the pursed-lipped Jenny and the uninhibited Lucy is almost uncomfortably real in pitch at times, a credit to both actresses.

For Sorvino, the force of gravity drawing her to Savoca’s script was the challenge to make the dichotomous spectrum of Lucy’s rollercoaster personality believable, while also understandable — even likeable. “The role was a hard role to play because I had to switch from those extremes like the gaiety, and [then] down into those depths of despair on like a dime,” explains the actress. “Something would set her off and oh, now she’s in a puddle of tears on the floor.”

High on drama and big on laughs, Union Square begs you to get tangled up in the branches of its family tree, as the characters unearth its roots in the search for who they are. The theoretical iceberg in the film’s narrative is a Titanic-sized one; from the shiny surface of appearances into the murky waters of history and memory, the film decodes the sisters’ respective survival strategies, as each is unmasked. From the director’s perspective, “it’s revelations about the characters” such as this, that make the dramatic ups-and-downs of the storyline work. “That’s the payoff…we’re surprised by who they are,” says Savoca. “They keep changing masks.”