The possibility, or more, impossibility, of a modern dramatist to pen a tragedy was a debate August Strindberg confronted head on with the writing of his 1888 play, Miss Julie. In creating what he contended to be the first Naturalistic Tragedy in the history of Swedish drama, Strindberg introduced a modern psychological drama adept at satiating the ideals of the classical tragedy.

As was Miss Julie a deliberation on the natural man, writer/director Catherine Corsini’s film, Partir (Leaving), is an autopsy of this same human, the fated victim of heredity, societal predispositions, and animal instinct.

The battle between life and death opens the film. A gunshot goes off in a slumbering house and the story recedes into months past, before the order of domesticity is fragmented by the unbridled laws of nature.

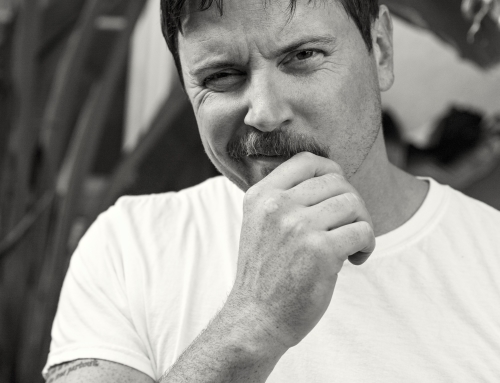

“I wanted to film something that wasn’t black and white,” explains Corsini, who screened her film at this past year’s Toronto International Film Festival. “It’s not about good guys and bad guys, more how situations can complicate life.”

Corsini shares Strindberg’s flair for psychological characterization. In her dissection of her characters’ milieu, she unfurls the mask of convention containing each character’s psyche.

Suzanne, played by Kristen Scott Thomas, enters the narrative as a light-hearted wife and mother of two, preparing to return to work as a physiotherapist now that her children are both teenagers. Overseeing the construction of her new home office is her husband, Samuel (Yvan Attal), a successful doctor and seemingly doting husband to his equally adoring spouse.

“I have always wondered about this tranquillity and calmness,” says the director of the seeming perfection of such domesticity. Partir (currently awaiting a North American distributor) is the untold story of life unravelling behind closed blinds.

Disturbance arrives on their doorsteps in the foreboding form of Ivan (Sergi Lopez), a former convict now working in construction to support his young daughter in Spain. Social cautions are abandoned and the marriage ruptured when time and chance extract an attraction between the two that Corsini presents to be incontrovertible in nature — an utter outburst of animalism.

Each character’s station in society is changed by the course of events following the coupling between Suzanne and Ivan. “They are pushed out of society and class boundaries,” explains Corsini. Suzanne leaves behind a life of comfort for odd jobs to help support an injured Ivan, while simultaneously Samuel is rendered impotent as a consequence of his wife’s uncouth departure.

While the lives of all three individuals are destabilized by the affair, it is Suzanne and Samuel that, like Miss Julie, are ensnared, cast out, and finally ruined by tradition. Suzanne, desperate to follow her passion regardless of taboos, “blossoms and finally finds strength in herself,” according to Corsini. Contrarily, Samuel, desperate to thwart social alienation, reverts to brutishness, “becoming a stranger even to himself,” says the director.

Describing the relationship shared by Suzanne and Samuel to be “a social game they play with each other,” Corsini speaks to the struggle for power Strindberg dramatized between Miss Julie and her servant, Jean. “You’ve seen it and I’ve seen it in real life,” asserts Corsini. “Love can turn monstrous.” The turn of emotion, from one end to the other, is what the director regards to be “a classical tragic story.”

The astute psychology of Corsini’s narrative is in its grey colouring. No single character is martyred or justified in their actions; they all exist in a claustrophobic vacuum of morality, where instinct reigns. “They are a complexity of what they are and do,” notes the director. Corsini’s is a tragedy of naturalistic proportions, in which, invariable nature and volatile society combat.

“As modern characters living in a time of transition — more hectic and hysterical than the preceding period, at any rate — I have drawn my characters vacillating, disintegrated, a blend of old and new,” once wrote Strindberg. “My souls (characters) are conglomerations of past and present stages of civilization; bits from books and newspapers, pieces of human beings, rags and tatters of fine clothing, patched together like the human soul.”

Partir is a composite of patched together human souls, searching for meaning in a transient culture. It is an inquiry into timeless nature, an exposition of the human condition; it is, at its core, a drama fit for Strindberg.

Trailer