Father John Misty’s latest masterpiece provides a poetic soundtrack that guides listeners through the dark, funny, and emotional return of Josh Tillman.

Tillman has been writing and performing under the moniker Father John Misty since 2012, but on his latest record, I Love You, Honeybear (Sub Pop)—the follow up to Fear Fun—the artist references his real name in the song, “The Night Josh Tillman Came to Our Apartment.” The first song written for, and “undoubtedly the darkest song” off the album, it begs the question, does this new record represent a return to self for Father John Misty?

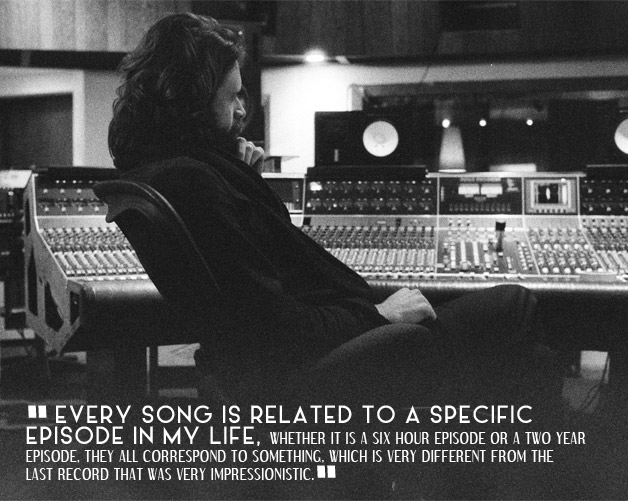

Sharing true, personal experiences of love, failure and triumph, Tillman’s candid songs provide snapshots into his life over the past four years. And, it is his moniker that the former Fleet Foxes drummer credits for giving him the freedom to be so vulnerable in his lyrics and his words. “I had been using my own name as an alter ego more or less,” but by assuming a new name, and exposing the fleeting nature of subjectivity, Tillman believes he is able to come closer to representing his true self. With I Love You Honeybear, “every song is related to a specific episode in my life,” says Tillman. “Whether it is a six hour episode, or a two year episode, they all correspond to something, which is very different from the last record that was very impressionistic.”

No music is off limits for Tillman, as he creates a perfect marriage between instrumentation and lyrics. Leaving his honky-tonk sound behind, the album shifts from simple guitar and vocal arrangements to synthetic ones, even throwing a mariachi band into the mix. Each melody is informed by the lyrics that fuel it, and throughout the album, Tillman opens himself up both emotionally and musically. Experimenting with ballads and love songs, for what feels like the first time, this latest work takes Father John Misty’s repertoire to new depths. “Don’t ever doubt this, my steadfast conviction / my love, you are the one I want to watch the ship go down with,” sings out “I Love You, Honeybear.”

Gearing up for the beginning of his North American/European tour in January, as well as the release of his new album, out worldwide February 10th, FILLER chats to Tillman about uncovering the inspiration behind his new album, the significance of his assumed identity and the return of Josh Tillman.

So you currently have some time off; where are you right now?

I’m in the bathtub, that’s what that sound of cascading water was…

Well, I’m glad you’ll be comfortable during our interview.

Yes, if I cut off all of a sudden, it is either because I have fallen asleep or dropped the phone in the tub.

Okay, please be careful! I wanted to talk to you about how each of your albums is musically and poetically more intricate than the last. What was the big inspiration behind this new one, I Love You, Honeybear?

For me, its really all in the lyrics. Those very much inform whatever arrangement we are going to go with. For example the “True Affections” song is more or less about trying to woo someone over long distances having only texting and whatever else at your disposal, and the frustration of that. So that sound really had to be entirely synthetic, or it had to be made entirely with cold synthetic instruments like keytars and electronic drum kits. That is one example. I think that there is some baseline fascination with doing something that you haven’t done before. I knew that I didn’t really want to make another honky-tonk sort of thing, there is other territory I wanted to explore. There are some ballads on this record, and having a tune with just piano, guitar and strings, I had zero interest in doing that last time around. On one hand its just what the song needed and on the other hand, its kind of a question of ‘can I get away with this?’

What inspired you to write that type of song?

Well, its just kind of what the song needed…“Bored in the USA,” the people that I was making the album with, heard that song in a certain way, with a lot of bombast, and they wanted cannons firing off at the end. This is kind of the main foil of this record in general—a lot of the songs initially presented themselves as needing… I kind of thought I knew what I was doing when we started the record. And I thought, ‘well, I just need to go with my initial gut decisions, and I was feeling really good about myself (laughing), and good about my instincts, but “Bored in the USA” took a year or something to realize that what that song really needed was a laugh track, and that was really the master stroke to the song…really the way that a lot of the songs went. On “Chateau,” what that song needed all along was a mariachi band. And that was after a year, year and a half of throwing every conceivable—what I thought was just instinctual—[idea around].

What inspired this change of thought towards your creative process?

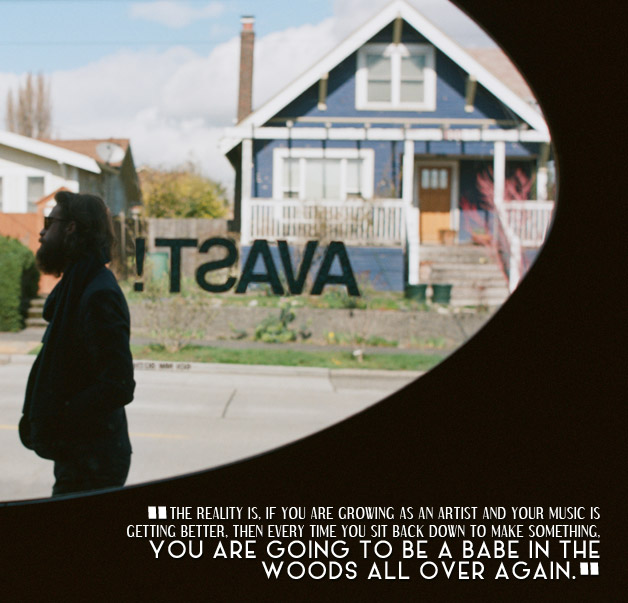

I thought, ‘well all I really need to do is what I did last time,’ because I had this big breakthrough, and I thought, ‘okay, well that is just what I need to do from now on,’ but the reality is that if you are growing as an artist and your music is getting better, then every time you sit back down to make something, you are going to be a babe in the woods all over again. And there is going to be some new discovery or you are just repeating yourself over and over again. I think that is part of why I took so long to make the record, I sort of had to forget everything.

And what was that process like?

I mean the writing of it is one thing. Recording is always the same, in that you start with very lofty ambitions and you get halfway through and you are like, I’ll just be lazy, I’ll whore myself out in any way conceivable just to get to the end of this thing because its driving me insane. And then it is a mystery that you have to answer for when people think that its great, you are like, if only you could see how the sausage is made.

But the writing is a different thing?

With the writing—and this is typical of my records—some of the songs are really old, maybe two-years-old, and some of the songs were written very recently, “Holy Shit” is the most recent song, that is the last song that I wrote for the record. So the timeline is basically chronological, from “The Night Josh Tillman Came to Our Apartment”—undoubtedly the darkest song on the album—to “Holy Shit.” The last three lines of this song, are the closest the album comes to representing my state of mind currently.

Can you explain the state of mind? What’s its time frame, what’s its mood?

Pretty much a three or four year stretch, and in between falling in love and thinking you know what love is all about, and fucking up, and essentially realizing that the state of mind that you brought into this thing isn’t going to suffice anymore, and what you really want is a companion with which to undergo total transformation.

So is then I Love You, Honeybear a concept album about that transformation?

Yeah, I mean I am kind of being funny, but it is conceptual, there is a conceptual thread throughout the whole thing.

If you think of the songs chronologically like that, there’s a change and shift in moods across the album, but every song has a stark level of honesty to it.

It felt very autobiographical at the time I think because the shift in tone and whatever felt so drastic and so personal. But, I mean this album…when I first started playing it for people…I just wanted to jump out of my skin, because I realized this is uncomfortably personal.

Any song in particular that stands out as especially personal?

You know with “We Met at the Store,” we are talking about a song that is just guitar, vocal and lyrics, and an experience like that brings up these personal vulnerabilities, and the only way to express that is through vulnerability in the arrangement and music. And that makes it sound like I have a lab coat on when I am figuring this out, but really they are just intuitive decisions.

It reminds me of Leonard Cohen. What kind of music do you listen to or what has influenced your writing of this record?

I am inspired by definitely Leonard Cohen, although I think that he and I—as a huge fan of his and someone very conversant in all of his music and [someone who has] read books about him—I think he and I are remarkably different people. But he is a huge inspiration. Just in terms of, this guy is confronting every cliché or modality in the rocker archetype, and I think that for musicians, there is a very well trod path for freedom and the success rate isn’t great. But it takes a really special kind of person to kill that idol, and I think that for someone in his position to talk so vulnerably and so personally, and to give up the vanity of being the rock star or whatever and be honest with himself and his audience about the things that he wants and needs as a human being, is really inspiring and is far more representative of what true liberation looks like to me.

It’s a difficult thing to achieve…that kind of liberation.

Especially in this day in age, there is kind of an obsession with individual expressionism and everywhere you look it is just this failed experiment. And to go out and say I am not a fixed individual, I need to change and I need someone to help me do that, flies in the face of the convectional thing today, which is that, the point of life is to know who you are, and know your appetites, and know your limitations, and know all that for certain, and to proceed accordingly and to disregard any input or advice that says otherwise. I don’t know if that makes sense, I am still figuring it out.

On that note, let’s talk about “The Night Josh Tillman Came to Our Apartment,” why did you decided to come back to yourself, to Josh Tillman, in this way?

To me it was always kind of Josh Tillman, the point of the name was to draw attention. The album has to do with the subjectivity of identity, and a lot of it was coming from this place. I had made a lot of music under my own name for a long time, and got to this place where I had been using my own name as an alter ego more or less, that I hadn’t communicated myself in a way that. There was a way of communicating myself that was honest, an the idea which scared me for a long time, because nobody wants to be vulnerable in that way and fail, and so, you create some kind of persona.

Enter Father John Misty.

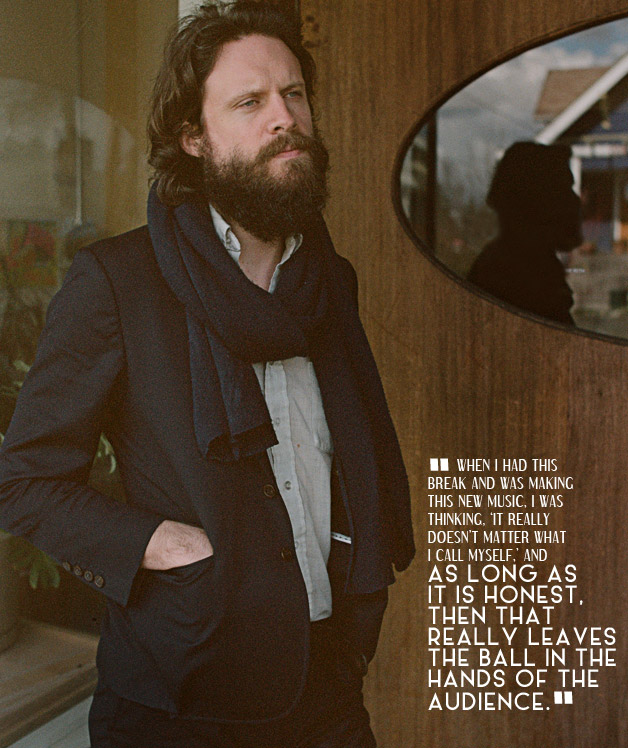

I wanted to sound like a person who was great, and that in a big way informed the music that I made. So when I had this break and was making this new music, I was thinking ‘it really doesn’t matter what I call myself’ and as long as it is honest then that really leaves the ball in the hands of the audience. I think what is interesting about this record and what may change the perception, is that an alter ego doesn’t evolve. It is a character that has certain traits that define it, but a human being is something that is very fluid and constantly in flux as I see it, so of course if the music is being made by a human being, it has to represent that. But, I just think its funny to throw my own name in song titles.

I think its cool that you’ve come full circle. The album’s press release comes with a letter from you talking about the album’s concept, though it kind of seems like you didn’t want to talk about what the record was about…

That’s just my bedside manner. There’s a danger in attaching words with images so to speak, I don’t want to contextualize it so much for the listener that by the time they get around to listening to it, their experience is tainted by my ideas, which are constantly changing or evolving.

That makes sense. So what can you then say about the album, without contextualizing things too much?

What I think about the record now, is completely different than I thought about the record as I was making it. Those sort of illusions that come and go over the course of doing anything are really important. Sometimes it is important to be in the dark in terms of what you are doing, so that you can keep doing it, because if you knew exactly what it was you were doing, you would be too scared, or too embarrassed or whatever.

How do you mean?

Like, when I was making the record, I thought I was making this kind of tough, funny thing, but then now, I hear it as someone who is in a large part, very frustrated and very hurt. I hear a lot more vulnerability in it now.