August 20, Day 1

150 km outside Paris

I do remember how Osita sleeps.

Just not in a bed, not in a bedroom. I never was awake for that — or if I was, I don’t remember because I was wearing a moronic sleep mask, and had a fan whirring louder than a train in the corner, unaware of the setting sun beside me every night.

But I actually have seen her sleep, elsewhere, many times. The memory came to me as I finally left Paris, in those first quiet, peaceful kilometers on the autoroute. The exaltation I felt from my grand conquest of Sofia and learning how to drive stick earlier that day was short lived. Soon, as the first rest stops outside Paris zoomed by me, those jubilant feelings melted into something else. A lightness transformed into a dark cloud in my chest, one that hurt, because I could only think of one thing: her.

I looked over to the empty seat to my right, and I could see her ghost there with me on the road, and it was then that I remembered it. She always slept on long drives. That is where I’ve seen it happen.

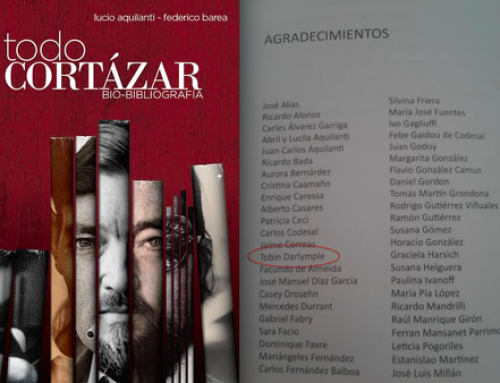

I am telling you this story because this blog traces the courage and creativity of two lovers – two lovers who knew how the other slept, and they described it marvelously in their book from the Cosmoroute. To me, it was my great shame I couldn’t recall how she did it – especially when she once so marvelously wrote about my sleep habits, the day we started calling each other Ositos. (She always was a much better writer than me.)

But she slept on long drives, slept when moving. And what a relief it was to know it. This was me feeling again, close, and then, immediately, far away again. The ghost right beside me. Beautiful. But the ghost a ghost, none the less. Lonely.

ON HOW OSITA SLEEPS WHEN MOVING

Of the many things we never had in common, of all the differences that still leave us a world apart — her distaste for vacationing in VW campers, for instance — we shared one very peculiar and unfortunate affliction: car sickness.

Leaving town, if we were lucky, we’d remember to bring the Gravol. “Do you have them?” I’d ask.

"I can’t find them!

There would be a mad scramble, as we were already late, as we always were, and then, scrounging through makeup-powdered drawers, and cutlery trays full of change and lighters, Osita would uncover the little white and pink package that would be her life saver.

Though if we forgot — we always did that too — I’d make a dash to the pharmacy, or pull over to the Shoppers on the way, because, if not, Osita would crumble with nausea, green faced, silent, fetal, a cronopia of the worst kind, as the road slowly swirled its meanness into her.

And so she would sleep on long drives up North to see my mother, to go to the cottage, to bring her to the world where butter tarts and lake swims are the only “to do’s”. Out of pure survival, she would sleep, and I would see it.

Here is how Osita slept.

The first stage is preparation, and it’s simple enough. First, the seat is pushed all the way back horizontally, and reclined as much as possible in one incredibly swift maneuver. Osita then proceeds to exhibit one of two possible positions: either her head resting side ways against the side of the door, the window open, a hand pressed to her temples, or she’d lay completely still, like a dormant vampire. Arms straight. Lips tight. A stone. No moving, or else face the bite of the road.

Preparation complete, Osita would doze off in a matter of minutes. Then I would be left, zipping up straw and green checkered fields, often as the sun was nearly setting, with the wind farms, the radio towers, the fruit stands, and Osita asleep, there beside me.

It was dangerous, but I would always dare to rest a hand on the sleeping bear, just on her thigh. A terrible temptation, because I risked waking up the little creature, and no one wants that. But I knew I must take it, because I knew there is no better feeling in the world, than driving up North, with a hand on her leg.

Without fail her sleep would be interrupted by the strangest of fears. All of a sudden, Osita would shoot up from the seat, breaking free from a dream about eating gelato on Av. America back home, and she’d place her hand on your shoulder, and ask you: “You OK?” She needs to know that you are alright, that you, the driver, aren’t also falling away into dream land. It must be that Osita can’t imagine what it’s like to not be so tired, as she lays slipping away with the moving road. So she will ask, every 15 minutes or so, otherwise, she’s certain we’d both go flying into the cow fields at 120 km/hour.

Two, three hours later, we would arrive. I’d unpack and as I stretched my legs, and opened the wine, Osita would still be dealing with the sickness, with the Gravol, with the ordeal of the journey. Now it is late. The friends are eating. Stories and gossip being told. And Osita will easily go back to sleep, at the dinner table, curled up on a couch, or removed all alone to the bed room, where she’d get under the covers, and fall away peacefully into a warm surrender. And then, a few hours later, I’d come in, flick off the lights, and put on my mask. The setting sun, the warm girl beside me, waking up as I got under the covers. The cold hands gripped together and the lips kissed. We’d say good night, te amo, and the morning would start its path.