With all due respect to the Biebs (whose current musical reinvention I am loving, by the way) the song “Sorry” could only have been written by a guy. It may be true that Justin “don’t do too well with apologies,” but for the vast majority of women I know, apologies come easily.

The word “sorry” slips from my own lips without a second’s hesitation, usually for one purpose: to keep the peace. People pleasing—an unshakable habit—has led to a lifetime of “sorry.” Whether at work or in relationships, being “sorry” for an opinion, a comment, a misstep or sometimes even just for being the closest person to someone who is angry, is a trite and meaningless go-to phrase that I have recently come to terms with overusing.

Truthfully, I was not even aware of how often I said “sorry,” until fairly recently. Anyone who has been in a mismatched, failing long-term relationship can probably relate to the fact that there comes a point that apologizing often becomes the simplest way to end a potential argument, even if you don’t happen to be in the wrong. Conflict-avoidant by nature, I would say “sorry” to steer the conversation away from turning into the same fight that had taken place so many times before. I knew the way it would play out already, that my tendency to placate would win out eventually, so I’d skip the yelling and tears and stick the apology landing as soon as we jumped. While this may be one of my worst and weakest qualities, I’m definitely not alone in this habit.

Much ink has been spilled about how women tend to soften themselves to avoid being labeled as some sort of shrill harpy, but I think Nicki Minaj put it best when she said, “when a man is assertive, he’s called a boss. When I’m assertive, I’m called a bitch.”

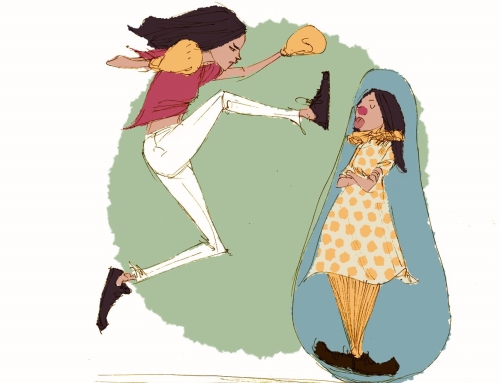

Over the years, I’ve said sorry for everything under the sun, but most of the time, the point was the same: “please like me still.” An apology can soften the blow when we’re right and the other person is wrong, or preface an argument so that we don’t sound as strong in our opinions. The “sorry” praxis is one of so many ways that women are taught to minimize themselves to be more appealing; from the loudness of our voices to our physical bodies themselves, we’ve been taught it all comes into play when establishing our level of attractiveness. In my experience though, the unnecessary, compulsive apology is as insidious and diminishing as any one of these lessons.

The ironic thing about “sorry” is that it’s also one of the last things most women I know want to hear. Those who’ve experienced those same failing relationships have felt the meaning of the word slip away each time it’s used. If something is worth apologizing for, the word doesn’t cut it; you have to show the person you understand how you’ve made them feel and correct it. If you’re saying it just to say it, it becomes just another sound, like street noise that barely registers after you’ve lived with it for long enough.

So what to do once “sorry” has worked itself into your unconscious habits? Like any program for breaking habits will tell you, the first step is acceptance. It wasn’t until I was in a happy, well-matched partnership that I realized how much I was leaning on the word as a crutch. It was pointed out to me as if it was a tic, much like biting one’s nails; my boyfriend couldn’t understand why I was always apologizing for things that he was not even remotely upset about. And then like that, suddenly, rather than just letting it slip out, I could now—once again—hear the word.

The next step is sorting out how often and what the triggers are for your apologies. If the overuse of “sorry” has developed as a coping mechanism for critical parents, you might find it comes unbidden under scrutiny from authority figures like your boss at work. If instead it has developed in a romantic relationship, it may be your go-to in conflict at home. Whatever the case, keeping track of how often and why you find yourself apologizing, is helpful to figuring out how exactly to rein it in.

Finally, the decision to consciously only apologize when it’s really deserved, is the last critical step. If you say it only when the word “sorry” is backed up by active proof that you understand why and what you need to do in order to make the situation right, the word will regain it’s true meaning.

Consequently, this change will also force you to have a bit more of a backbone. Standing up for your opinions, or comforting someone without taking responsibility for pain you didn’t create is healthy, and, will make you better at being an employee, partner, and friend.

Knowing when you’ve really made a mistake is empowering. Owning your mistakes and making them right is being a boss. And if you backslide into sorry because you’re afraid of not being liked, just remind yourself of the gospel according to Ms. Minaj: “Bitch, I am the boss.”