The culture of a society is embedded into their popular fashion. A social-political statement, fashion is a product of its time, capable of telling the story of its generation in the hem length of a woman’s skirt or the collar of a man’s shirt.

In film, costumes anchor the story; each outfit is a window into the character’s life, and the period they live in. The magnificent formal dress of Queen Elizabeth I had purpose over style in her age, and saw to affirming her superior status. In Elizabeth, the audience is immediately struck by the stark distinction between Cate Blanchett’s character of the Queen and her courtiers, and by way, delivered into the politics of the day.

Like the screenwriter behind a film, a costume designer is a storyteller. In director Howard Hawks’s His Girl Friday, it’s Hildy’s never ending hat swap that communicates she’s at a crossroads. Switching between more feminine hats and masculine ones, her choice is dependent on her whim to become a devoted house wife one moment, and continuing on in the male dominated journalism racket another.

With director Joe Wright’s Anna Karenina in theatres come November, but already infiltrating mainstream fashion trends (see Costume Designer Jacqueline Durran‘s collaboration on a fall capsule collection with Banana Republic in stores later this month), what better season than this for the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A Museum) to launch their Hollywood Costume exhibit. Opening October 20th, the exhibit sees 100 of cinema’s most iconic costumes — from Holly Golightly to Indiana Jones — on display till January. In anticipation for its opening, we talk to the curator of Hollywood Costume, Sir Christopher Frayling about the museum’s selection process and the unsung genius of Hollywood’s costume designers.

When compiling the collection for the Hollywood Costume Exhibit, how did you begin narrowing down the selection?

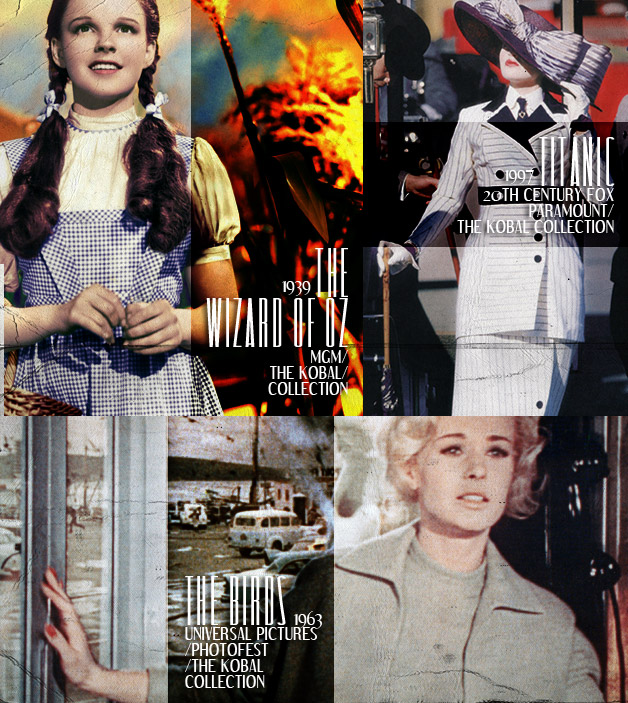

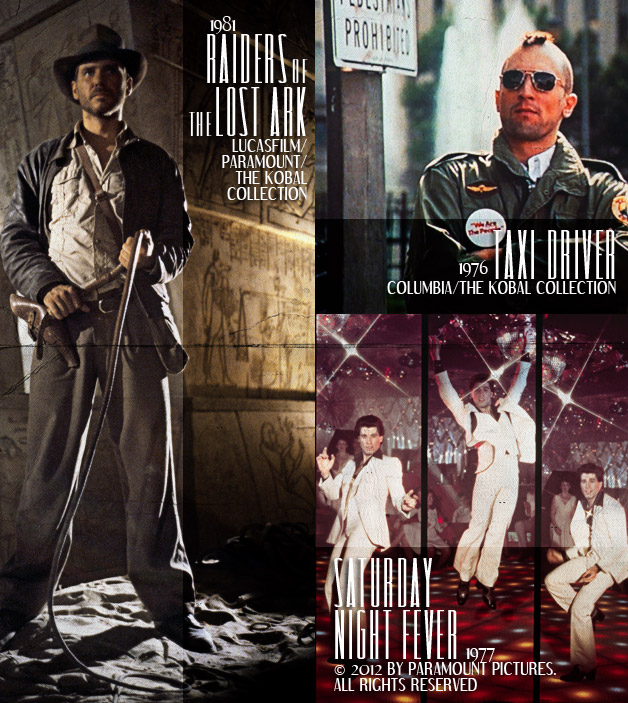

There were some “must haves:” The Wizard of Oz, Chaplin’s Tramp, a Marilyn Monroe, Audrey Hepburn, and Indiana Jones, for examples — but we decided early on that this wasn’t primarily a “greatest hits” show, more of a show about film costume design as a distinctive form of design. So a wide range of modern and contemporary material was essential too. Plus there was the question of availability and “have the costumes survived”? A lot have faded away.

In the history of cinema, which costume designer’s oeuvre do you admire most?

Edith Head from the studio era — she was the last of the in-house Hollywood studio designers — specially for her work with Alfred Hitchcock, who had a very strong visual sense. A great example of teamwork too. We have The Birds in our show. Of the current ones, our senior curator Deborah Landis — she of Indiana Jones and the Blues Brothers — is a favourite too.

Do you think that cinema and television often set fashion trends more so than runway fashions due to the accessibility of the medium?

It’s a two-way street. Cinema picks up on what is “in the ether,” and then popularises it on a grand scale. In films set in the present day, its important for designers to be up-to-date — so audiences will recognise and respond — but the films are also planned well ahead, so up to date and slightly out of date at the same time.

As a narrative element, what role does the wardrobe in a film play?

Costumes are there to be part of the story, so that the words on the page of the script will come alive visually. They have to “work” when worn by a particular person, at a particular moment, under particular lights, at a particular stage in the story. Under a particular director. All of this differentiates film costume from fashion on the one hand and theatre on the other.

Do you believe the wardrobe of a generation speaks to the spirit of the times as much as the written and spoken words put forth during that time?

In retrospect, film costumes — like costumes in paintings — come to “stand for” an era, telling us things that words on the page can not. And costumes in historical films tell us as much about the time the film was made as about the historical period of the story. In the show we have two Cleopatras, one from the 1930s one from the 196os. They now look like 30s and 60s costumes, but they didn’t at the time. People didn’t notice. They just thought the costumes and makeup “worked” for the ancient world. So its complicated. But as historical evidence in retrospect about social history: unbeatable! Film costumes distil the present day.

You’ve been quoted as saying, “the design of costumes for films is often take for granted or misunderstood;” do you think that in general, the iconic significance of fashion is underestimated?

Film costume is certainly taken for granted. Someone once said of it that “if its invisible its good.” In other words, it’s completely part of the story rather than taking a bow on its own… fashion, too, is underrated, as are most visual things in Britain. We’re traditionally more comfortable with the verbal than the visual, on the whole. But this is changing…

What is your favorite film represented in the exhibit?

Marilyn Monroe’s gravity-defying costume from the end of Some Like It Hot. How they got away with it is anyone’s guess. I first saw it at a very impressionable age!