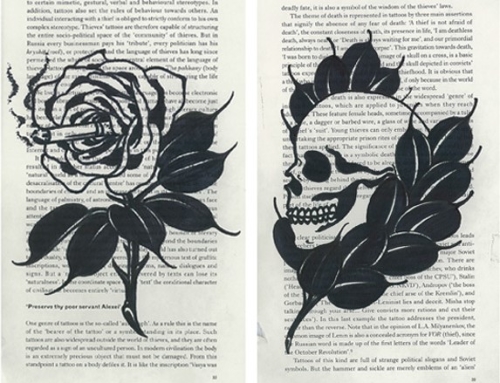

Gothic, Darwinian, and quieting in its still reflection, the photography of Canadian artist Deborah Samuel captures the spirit of her subjects in haunting monochromatic likeness. “The only way I can describe it is that I feel things,” says the artist of her work. “It’s pretty important to me that whatever I’m shooting, I capture the essence of something.”

Based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Samuel returns to Canada for her most recent exhibit: “Elegy,” currently on display at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) until July 2nd. Of the 33 images on display as part of the exhibit, 10 have been commissioned by the ROM to highlight specimens from its own collections. “Elegy” marks the inaugural collaboration between the ROM’s Life in Crisis: Schad Gallery of Biodiversity and its Institute for Contemporary Culture.

A contemplation of life after death, “Elegy’s” theme was born from the artist’s personal experiences and losses. The poetic imagination of each photograph is anchored by the reality of life’s fragility, transience and persistence; a narrative told through the image of rigid bones and shells belonging to creatures who have long since vacated their pulsating flesh.

Rattled by the environmental disaster of The Deepwater Horizon oil spill that devastated the Gulf of Mexico in the summer of 2010, Samuel set out to document the story of the many thousands of lost lives that comprised the oiled wildlife, specifically birds, affected by the spill, but was prohibited from doing so by both the government and regulations enacted by BP, the global oil and gas company which operated the Macondo Prospect where the spill originated.

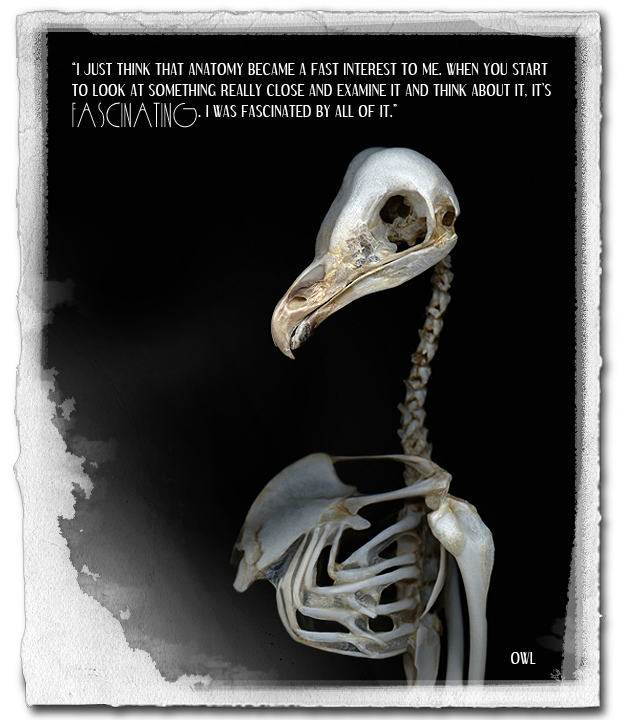

This desire to work with bird skeletons soon evolved into a great fascination with overall animal anatomy. An ardent and long-time animal rights advocate, Samuel began further research into the animal world, satisfying a particular personal curiosity concerning their interpersonal relationships, examining how bonds were manifested.

As seen in her photography, Samuel’s interest in wildlife stems far beyond an animal’s physical attributes; it is their emotions and the relationships they forge and nurture that holds her camera’s focus. We caught up with the artist before the premiere of “Elegy” at the end of last month to talk about the never-ending evolution of her creative vision and her fascination with science, spirituality and anatomy.

Take us back to the beginning. How did you break into the art scene? Was it one of those inevitable things in life?

I went to art school for a year and I actually wanted to be a potter, I wanted to do ceramics. But then I just totally fell in love with photography. I was always out with my camera taking pictures, but I could never figure out how it could be a career for me.

You later ended up at Sheridan College after moving back to Canada from Ireland, where you attended high school. Were you pretty much on the path to professional photographer after that?

I did a two-year course in photography, and still couldn’t figure out what my career would be, but I really wanted to get into the arts. I started doing promotion shots for my friends and I made a living doing that. Then I ended up going into fashion because I got to travel and see amazing places and do amazing things.

And did you do your own thing on the side?

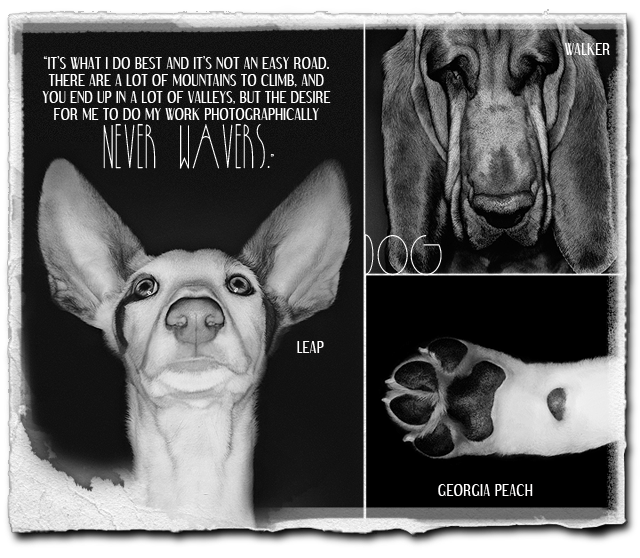

I always had my own work; it was just as present as my commercial work. When I was working commercially I also did a lot of exhibitions of my own work. I always had that art career and about 12 years ago I started working with dogs. I became really attached to working with dogs. I wanted to figure out what made them all tick, not just their physical differences, but their emotional differences.

And then 2 books on the subject later?

Then it was very clear to me that it was very important to concentrate on my own work exclusively. That was probably around 10 years ago.

Since that career redirect, what has become your central artistic style?

I think I have a unique vision and I think the only way I can describe it is that I feel things. It’s pretty important to me that whatever I’m shooting, I capture the essence of something. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a truck or a dress or a dog or a horse — it doesn’t matter, it’s the essence.

As of late, it seems animals have an essence you are particularly interested in capturing.

I’ve worked a lot more with animals in the last 10 years because I really love animals and their emotional being is what has really interested me to work with them. What makes them all tick, if that makes sense.

Is that the heart of your motivation as an artist, figuring out what makes breathing souls tick?

In the last 5 years I have had a lot of loss with my father, with animals—my horse specifically and 3 dogs all from severe illnesses—and I think that life-death divide became the question that kind of consumed me. When we die, what happens and where does this energy go?

The cycle of life saturates your imagery of animal skeletons. What inspired you to begin shooting skeletons?

Two years ago when the Gulf oil spill happened, I was really horrified by the photographs I had seen of the oil-covered birds, and I found that really difficult to look at and to think that we as humanity have done this to the animal world. I tried to go to Louisiana to photograph these birds because I thought it was iconic with respect to environmental concerns and animal concerns, but I couldn’t get in because there were [government] restrictions. Then I kept thinking about it and I thought of death and the skeleton, and I started to look for bird skeletons. I felt compelled to do it.

How so?

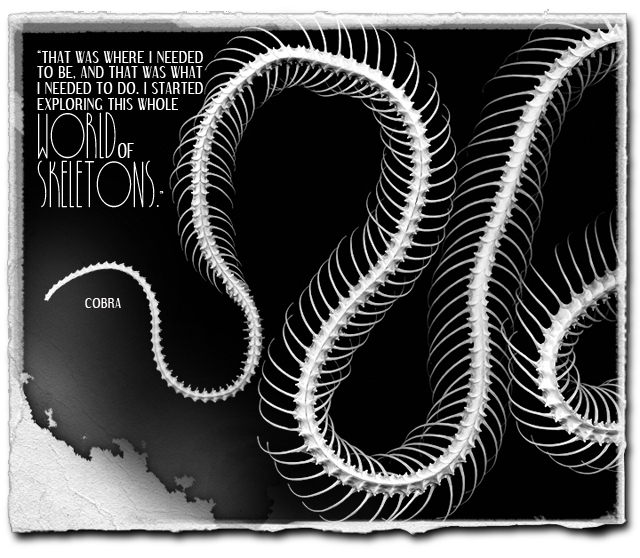

That was where I needed to be, and that was what I needed to do. I started exploring this whole world of skeletons. Primarily I started with birds and fish because those were the ones that were more affected by the spill, but then it continues further on with different species.

What narrative do you want to communicate to your viewer?

I think that the point of this work really is that when you look at it, there is an animation of the skeleton, and its what is left of their life—that was what’s important to me, and made me wonder what their world was like. How these birds in particular…how they stayed together, how they looked after each other, how they survived, what their emotional life was like. That is what stirred this work…that there are inter-relationships. When you look at them, you actually see them as whole beings.

Your work with skeletons really conjures up scientific intrigue. What about anatomy and science appeals to you as an artist?

I started looking at these things and I was amazed! Who built this? Who is responsible for this? And, how we’re all built, not specifically animals, how we’re built to sustain and survive. I just think that anatomy became a fast interest to me. When you start to look at something really close and examine it and think about it, it’s fascinating. I was fascinated by all of it.

How do you want your audience to interpret this fascination?

I think what’s important is that people can look at this and have a sense of the world around us. How amazingly beautiful each element is because if we stop and look at these elements, our life is very full and very rich. We can appreciate every little thing that exists on this planet with us.

How do the photographs included in “Elegy” differ as a whole from your past work?

I am kind of known for doing subject matter. My subject matter jumps around and I’ve been known for that, which I think is a part of humanity. I found strangely that I’m more drawn to the animal world in this period of my life. My last body of work was dogs, and then I actually did a series of botanicals, which actually came out of my relationships with my animals. And then I got into elegy. I’m more drawn to examining animals at this period.

Why choose photography as your preferred medium?

I would have to say photography is my clearest voice. I’m not sure it would be so clear in other mediums as naturally. I appreciate them, but photography is where I find my voice. It’s just a medium that works for me.

Any artists who you would cite as influential in terms of your own vision?

Photographically, it would be Horst. I admire so many different artists, I admire their vision and I admire their life.

On the life of an artist, it’s a difficult one that many want, but do not always succeed at. Often commercial jobs are the only source of income. How do you as an artist find harmony in art as a job and art as a passion?

It’s what I do best and it’s not an easy road. There are a lot of mountains to climb, and you end up in a lot of valleys, but the desire for me to do my work photographically never wavers. There are always tests that come up. I think for me it’s my voice and it’s a lifestyle. You have to be prepared for the good times and the bad times. Being an artist, those mountains are a lot different than when you have a job where you can depend on a cheque coming in every week, and your life is on a course where you don’t have to worry. For artists, it’s really a lifestyle choice.

And for you, is art your life?

For me, I keep working all the time. Even if it’s a difficult period, I still keep working. Part of the desire to do that is working through issues that concern me and it’s important for me to do that. I just feel that’s why I’m here…because it’s my job to do that.