It started with a desire to understand society’s notion of beauty, and from there, Nandipha Mntambo’s animal instinct took over.

One of four artists selected to showcase works at the Art Gallery of Ontario as part of AIMIA | AGO Photography Prize — one of Canada’s most significant art awards — Mntambo has achieved international acclaim, even without stepping foot in the nation behind her most recent distinction, Canada.

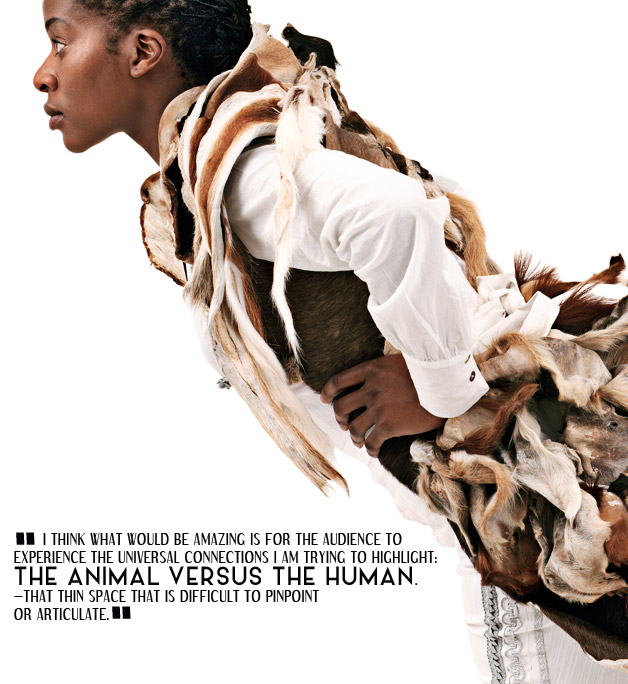

As I gage early into our discussion about her body of work, it is apparent that Mntambo is an artist who creates with both her mind and soul — with both intelligence and emotion. The topics she hopes to unfurl through her artistic expressions are, as she shares, universal concepts that have existed for centuries; issues that cover the expansive territory of male vs. female, animal vs. human, attraction vs. repulsion, and social perceptions of race.

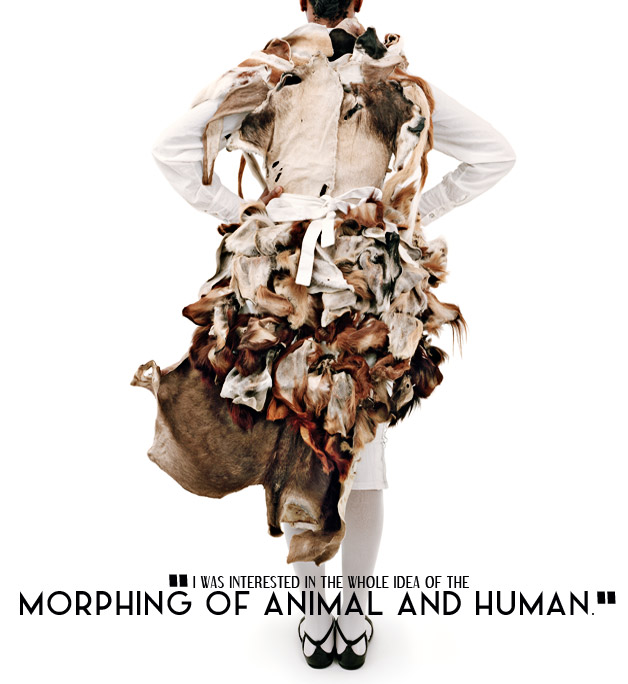

And as mentioned above, the root of it all really started with the artist pondering the very idea of beauty. “I wondered why hair is connected to this idea of beauty, especially with women, and how we understand a completely hairy female form,” explains Mnatmbo. From her work, it’s clear that this form she speaks of, is the animal life we share our environment with and the difference between the public’s perception of a beautiful human verses that of a beastly animal. “I guess that’s where it started, with attraction and repulsion.” To illustrate her theories, Mnatmbo uses her own body as the form for creating her cowhide sculptures. In essence, she takes the hairy medium, envelops her body and then, using taxidermist processes, she moulds and solidifies it to the lumps and humps of her own body. The humps, in this case are imperative, for according to the artist’s perception, this is what defines the human form, a series of humps.

Realizing she may never uncover the answers her body of work seeks to discover, she hopes audiences will grasp the connections she is trying to draw between her subject matter. For Mntambo, her work is meant to drawn the viewer to a line, where they are left to understand each side, and the balance between. She wants them to experience “that split between being totally attracted to what they are seeing, but a little bit disturbed or repulsed by it, that thin line where you are not really sure which side of the fence you are on.”

While as the artist concludes, the issues explored through her work may be too complex to ever truly resolve, the subject matter is embedded in the history of human kind, and so are the answers, be it in the past, present or future. Below, FILLER chats to Mnatmbo about her kinship with animals, the depths of her exploration into universal issues and the message behind her canvas.

To start, I’m interested in learning more about your connection to the animal form. I understand you had a dream about cowhides, and then decided to bring this alive, and that overall you believe, everyone is somehow connected to cows, no?

You know the funny thing is, I don’t think I have really discovered what my connection is yet. (Laughing) I think it is a journey I am still on.

What are some of the connections you think other people have with cows, then?

I mean, the reality of it is, a lot of people eat beef and wear leather — unless you’re a vegan. In all civilizations of the world, this animal has had a case, whether it is in ancient Egypt or modern day India, everyone just had some kind of interaction or association with the animal.

Okay, so quite a literal connection then! And then from contemplating this relationship between humans and animals, you started to think of hair, and beauty, and ultimately perception of beauty, right?

I think that is where I sort of started, the whole idea of attraction and beauty, and how we understand repulsion, and what we don’t find beautiful. Growing up, I went to an all girls schools, and I was always sort of left out of the groups because I don’t have a lot of body hair, so shaving and waxing wasn’t something I could do. I wondered why hair is connected to this idea of beauty, especially with women, and how we would understand a completely hairy female form. I guess that’s where it started, with attraction and repulsion.

And what about the deep connection with animals, how did that find its way into your contraptions?

Because of my interest in mythology: how we understand the animal versus the human, how human beings try to separate themselves from their animalistic aspects, and why we do that. I was interested in the whole idea of the morphing of animal and human, the Minotaur. And…I guess that all comes back to a hairy female or humanoid form.

Boils down to the hair. Do you think you will have any animal rights activists after you given the nature of your work and your use of animal hides?

I think some people have already had bad reactions to the work. What’s interesting within that though is the animals that I use aren’t killed by me number one. Number two, the material would exist if I was using it in this way or not. Number three, for me it all comes down to the whole element of humanness, about the fact that we are very capable of killing, but nobody wants to either admit it or have it in their face. I think that human beings hide from a lot of the nasty things we are able to do. I suppose there might be an animal rights activist out to chop my hair off, but the reality is, in a strange way, we are capable of killing and we’re trying to hide ourselves and other people from it.

What about the human form in your work, you choose to use your self as the subject. Why? Would it not be easier to work with the body of someone else and see what you are creating from a distance?

I have always had a love-hate relationship with the politics of representation, especially with the politics of representing other people, where they are not in control of how they are imaged and you are. I think that for me, it is comfortable for me to use myself and my mother. I have used two other women before, but had a really complicated relationship with that. So, I think being in control with how I want to be imaged, versus how I want to image someone else, is a comfortable space for me.

That makes a lot of sense, it feels more honest. You mentioned working with your mother as a model, which dates back to your 2007 series, “Silent Embrace.” Why did you decide to work with your mother and how was it working with someone so close to you?

The relationship between mother and child, especially mother and daughter, is a complicated issue. At that time, I was trying to understand how we feed off each other, how, in some ways I look like her, but in other ways I don’t. I have mannerisms similar to hers and others are not so much. So how much of the learned behaviour is totally me versus sort of the inherited behaviour that comes with genetics. My mom and I, probably like most mothers and daughters, have quite a complicated relationship. I think that there is this push and pull, where at times we’re closer than at other times, and sometimes, one of us imagines that we know everything about the other, but its probably not the truth. It is this dynamic where she should be the closest person to me because of how I came into the world — I was made inside of her and needed her in order to survive at one stage — but now I am separate from her, and she is not the closest person — emotionally — to me. It’s a weird dilemma around genetics, socialization, emotion, and also, how I understand body politics, how I understand the politics of being a women, and how that has been influenced having her in my life through the things that I have learned or that’s been inherited by her.

Going back to your origins as an artist and your vision, I read that you actually originally wanted to be a forensic pathologist. What motivated you to switch career paths and pursue art?

Well, at the time the forensic pathology that I was interested in was more human based; I wanted to understand how people died. Then I did a job shadow stint at a morgue and realized that is wasn’t what I wanted to do, I think being exposed to the dead on an everyday basis was scarring. I changed my mind, and I was lucky enough to have done art in school, so I had a portfolio that I took to the art school and it accepted me.

And did you find your voice as an artist there?

In my fourth year of undergraduate study, I was struggling with what medium to use because at the time, I realized even more how people understand art, how people understand black artists, how people understand black women artists, and the materials that they associated with this particular group of people that I was apart of. There was this strive to push me towards woodwork or pottery, and it just wasn’t an interesting thing for me. So I struggled for awhile until I had this dream [about the cow], and then I found a taxidermist that taught me how to tan cowhide.

You’ve mentioned in past interviews that you want to be labeled as nothing more than an artist, not a “female” artist or a “black” artist. Do you feel that you actively have to defy those labels?

When I was younger, but now I guess I am becoming a little bit more comfortable articulating what the work is about, and what it isn’t about, [as well as] how I would like to be viewed and how I wouldn’t. That sort of anxiety or need to constantly remind other people as to what I don’t want to be labeled as, has subsided.

Your works are discussions about the boundaries between gender, race, attraction and repulsion, and animal vs. human — topics that are not so easily summed up. What are you interested in uncovering with all this?

I think the universality of the issues. I think for centuries people have been trying to understand and uncover the connection between the animal and the human. If you look at different mythologies of the different civilizations, there are images of different animal and human morphing. And this whole idea of male versus female has been a preoccupation for centuries, I don’t know if I will ever really find the answer. It’s been a question in peoples minds for such a long time.

At least you’re exploring it. In your bull fighting series, you touch on the issues you mentioned. In the series, you are the subject, and you are wearing the animal hide. How does wearing the hide change the meaning of your work?

I was watching a lot of bullfights when I was in Spain and Portugal. [While] job shadowing some bull fighters, I began to understand that the garment is very important; the time they take to put it on, that meditation of putting on your performance outfit, it is an important element of bullfighting. I guess with the series, I was preoccupied with a combination of things: the idea of being in my work as a moving object and wearing something that I created, and the whole idea of the preparation that it takes to be in the ring.

I understand that a friend of yours who is a fashion helped with the garment in that particular series. Do you think that you would ever collaborate with a fashion designer on a collection?

Yeah, I think it would be great! I am enjoying collaboration a lot at the moment, I used to be a lot shyer to work with other people, but that is changing.

On the topic of fashion, the AIMIA prize asks photographers where fashion ends and art begins, where do you draw the line in your work?

I guess the way that I work, when an element — a “fashion garment” — comes into my work, the origin of it is a sculptural piece. So for me it, is a continuous line, it’s something that feeds off each other. The final product is influenced by the beginning of the process, whether it be the colour of cowhide that I get, the thought around what shapes I am going to use when draping it, and if I choose to wear it, it becomes a totally different element, part of the whole idea of a garment. It’s all one thing.

So quite a blurred line then! How do you want the audience to perceive or respond to your work?

I think what would be amazing is for the audience to experience the universal connections I am trying to highlight: the animal versus the human, that thin space that is difficult to pinpoint or articulate.

What would it mean to you if you won the AIMIA prize?

It would be a great affirmation. As an artist, I enjoy working alone a lot of the time, I am alone in the studio and sometimes don’t really think of the external things happening in the world, and how people are perceiving and receiving my work. [The prize] would be a reminder that I am not really alone, and there are things that I am obviously doing right that are making people interested and attracted to the work that I do. The fact that I have never been to Canada and this prize is at the AGO, it also helps me understand how big and small the world is. It’s just affirmation that I am travelling in the right direction.

Published September 3, 2014